After a delegation from UiT travelled to India last year, agreements on exchange and collaboration in research and education with Indian partners have grown in scope. This particularly applies to cooperation in optical technology and engineering.

The new year began with a formal ceremony marking the establishment of two new collaboration agreements between UiT and IIT Dhanbad in India, where also Norinnova TTO and the Academy of Scientific & Innovative Research (AcSIR) will contribute as partners. This means that Norwegian and Indian PhD candidates and master’s students will be trained in the fields of microscopy and artificial intelligence. They will also develop a variety of applications which can be used in fields such as life sciences, environmental and climate sciences, and earth sciences.

Researchers will learn to be in the same room, discuss science together, understand each other’s language, and contribute to developing the same ideas from different academic perspectives.

A total of 5.8 million kroner has been allocated to two projects that could create new educational platforms. The projects received 2.8 million kroner from the Indo-Norwegian Cooperation Programme in Higher Education and Research (INCP) and 3 Million kroner from the UTFORSK programme.

‘The projects are part of a positive trend at UiT, where an increasing number of groundbreaking projects succeed in fierce competition. These projects are innovative both in terms of using new technology in areas of great societal relevance in the Arctic and by working closely with users and industry,’ says Jan-Gunnar Winther, Pro-rector for Research at UiT.

Sharing of technical knowledge

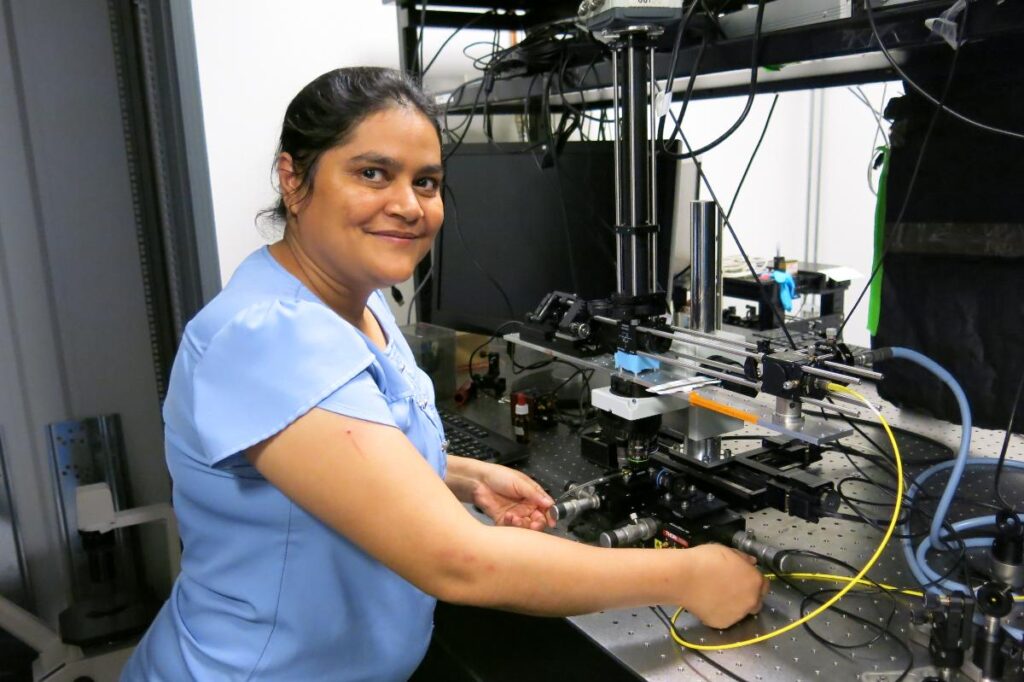

The project Bioscopy – Towards Modern Transdisciplinary Education and Research in Microscopy is supported by INCP. It is led by Professor Krishna Agarwal at the Department of Physics and Technology. Four interdisciplinary educational courses will be organised for PhD candidates and master’s students. In addition to IIT Dhanbad, AcSIR is also a partner in the project.

One of the goals of the courses is to create entirely new tools for research education. Younger researchers will then find new ways to use super-resolution microscopes to conduct biological analyses employing artificial intelligence. The tools are to be built at low cost, in a simple manner, and adaptable to a variety of contexts and research purposes. Participants in the courses will also develop digital curricula to enable the use of this technology.

Bridging the knowledge gap

Agarwal believes that this is a modern and transdisciplinary educational programme that can bridge a previous gap between theory and practice in fields such as physics, chemistry, biotechnology, and AI. She points out that various academic communities using advanced microscopes do not share technical and application knowledge sufficiently. She believes this has led to the technical capacity of microscopes not being fully utilised in certain disciplines, which has, among other things, limited the scope of biological research in several areas.

Agarwal emphasises that the academic communities themselves wish to create conditions for interdisciplinary research training and discussions and communication that enable a broader understanding of technical development.

‘With certain exceptions, it has been difficult for different academic communities to be in the same room and contribute to the same brainstorming sessions. The new courses in this project will change this situation. Researchers will learn to be in the same room, discuss science together, understand each other’s language, and contribute to developing the same ideas from different academic perspectives,’ says Agarwal.

Education in AI innovation

The other project, Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Environment, Earth Sciences, and Remote Sensing (SEER), is led by Dilip K. Prasad, a professor at the Department of Computer Science. The project involves holding specialized courses for PhD candidates, based on interdisciplinary platforms. The candidates will then contribute to developing new analytical tools that can be linked to AI programmes. These tools will be used for environmental monitoring, climate modelling, meteorology, and eco-friendly tools to counteract climate change.

Prasad believes that UiT’s collaboration with Norinnova and IIT Dhanbad in the SEER project is exactly what is needed to address the challenges we face in our time.

‘Both UiT and IIT Dhanbad have expertise in geosciences, environmental science, and climate science. Their geographical locations in Arctic and tropical regions allow them to complement each other and facilitate holistic perspectives on research. This yields significant benefits in addressing a challenge like global warming,’ he says.

Indian universities and research institutions are highly respected internationally for their expertise in IT, innovation, and entrepreneurship. They also have an increasing R&D focus on the Arctic, where many of the priorities align with Norwegian strategies.

Grants for Collaboration between UiT and Indian Partners

- UTFORSK is a programme that provides support for collaboration in higher education between Norwegian universities and partners in Brazil, Canada, India, Japan, China, South Africa, South Korea, and the USA.

- The Indo-Norwegian Cooperation Programme in Higher Education and Research (INCP) provides support for collaboration in higher education between Norwegian and Indian universities and research institutions.

- Both funding schemes are announced by the Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (HK-dir).

- INCP is announced in India by the University Grants Commission (UGC).

- In 2024, 50 grants from UTFORSK went to four UiT-led projects.

- Three out of twelve grants from INCP went to UiT projects in the same year.

In addition, Prasad points out that UiT and its partners have highly AI competent research groups.

‘This makes it possible to reach an upper limit of what can be achieved with AI. Field research requires highly energy-efficient and sustainable data resources for computations, and this is an area where IIT Dhanbad has been working for a long time,’ Prasad notes.

Pro-rector Winther believes that UiT’s increasing collaboration with Indian partners can have many positive ripple effects.

‘Indian universities and research institutions are highly respected internationally for their expertise in IT, innovation, and entrepreneurship. They also have an increasing R&D focus on the Arctic, where many of the priorities align with Norwegian strategies, such as in climate and environment, space, and oceans. It is both natural and desirable for our researchers to work with leading international research communities, and this certainly includes India. Collaboration with Indian partners enhances the academic quality, which in turn increases the chances of developing new projects,’ concludes Winther.