For close to a month, President-elect Donald Trump has warned that the Panamanian government needs to reduce the shipping rates and fees placed on U.S.-based vessels going through the Panama Canal, unless it wants the U.S. to take back the canal. At a gathering for the conservative Turning Point USA organization on Dec. 22, Trump proclaimed, “We’re being ripped off at the Panama Canal like we’re being ripped off everywhere else.” He then insinuated that the Canal could fall into the “wrong hands” — China’s. Immediately after, Trump posted on Truth Social, “Welcome to the United States Canal!” with an AI-generated image of a U.S. flag missing two of its 13 stripes.

Trump also has mused about making Canada the 51st state and acquiring Greenland. His expansionist focus has sparked a media fervor. Some have wondered if Trump’s business interests might be driving the President-elect’s thinking. But such speculation fails to account for the potential political boost that Trump might get from talking tough on the Panama Canal.

History indicates that it could be a good issue to unite the fractious Make America Great Again movement. In the 1970s, diverse forces on the right came together to fight against ceding control of the canal to Panama, seeing the move as weak and antithetical to American interests. The issue papered over divisive disagreements among conservatives over social and cultural issues. Now in 2025, it’s possible that Trump’s threat may be a way to use America First policies to once again unify a diverse conservative and populist coalition.

By the mid-20th century — with anti-colonial independence movements erupting across the globe — Panamanian frustration over U.S. control of the Canal began to boil over. A wave of nationalist protests ensued, some of which became violent and led to the deaths of U.S. soldiers. Recognizing the explosive potential of such frustrations, American presidents — beginning with Dwight Eisenhower — explored potential compromises that might ease resentments without giving Panama control of the canal immediately.

But while presidents in both parties saw this as a necessity to prevent more conflicts within the Western Hemisphere, the idea of giving the canal to Panama enraged the right. Conservatives had long been skeptical of such calls, and they thought the negotiations epitomized everything wrong with both political parties, and the liberal consensus politics that the right had been fighting against for decades. As William Loeb, editor of New Hampshire’s conservative Manchester Union Leader, summarized, “If we can block this it may stop this precipitous retreat to retire from everything.”

Read More: Donald Trump Still Wants to Take Control of Greenland—And Now Canada and the Panama Canal, Too

The intensity of opposition on the right became clear in the 1976 Republican presidential primary. Former California Governor Ronald Reagan’s challenge to President Gerald Ford was flailing when he began blasting Ford for calling for negotiations with Panama. Reagan denounced any compromise as a giveaway of American sovereignty in the face of international challenges and these calls helped resurrect his campaign. Although Ford eventually triumphed narrowly, Reagan demonstrated the political potential of using U.S. control of the canal to signal support for American hegemony in a way that energized and united different factions on the right.

Jimmy Carter ended up winning the presidency that year, and he promised during the campaign not to cede control of the canal. Yet, he changed his mind after winning the election and in September 1977, he signed treaties that would turn the canal over to Panama at the turn of the millennium.

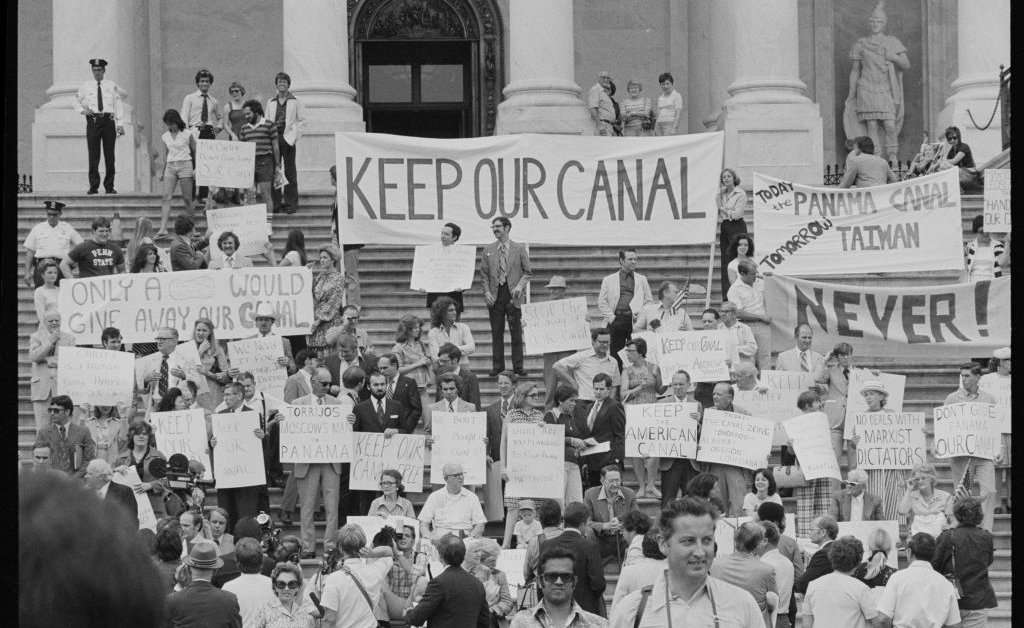

Right-wing opponents of the move began organizing to oppose ratification even before negotiators had finished hashing out the terms of the agreement. Once Carter signed the treaties, it kicked off an all-out mobilization that brought together a previously uneasy coalition of right-wing groups—including the rabidly anticommunist conspiracy theory-laden John Birch Society (JBS), Phyllis Schlafly’s growing antifeminist and pro-America conservative group, and those aligned with formerly vocal segregationists like North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms.

The JBS unleashed mailing labels and bumper stickers demanding, “Don’t Give Panama Our Canal! Give Them [Henry] Kissinger [Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford’s Secretary of State] Instead!” Meanwhile, Schlafly joined Loeb and other conservative leaders on the Emergency Committee to Save the U.S. Canal Zone to lambast any cession of the Canal as threatening the nation’s security. They cohered around “Keeping the Canal” — despite disagreeing on other matters with fellow members, such as the antisemitic Pedro del Valle. Likewise, activist and operative Paul Weyrich spent around $100,000 on his own “Keep the Canal” efforts even as he worked against legalized abortion and in favor of slashing business regulations.

The effort became a centerpiece of a burgeoning push to grow the grassroots conservative movement using a new technique: direct mail. One of the pioneers of the industry, Richard Viguerie, was an expert in discovering issues that could arouse emotional responses and generate donations and support for a variety of conservative causes. He understood that the fight over the Canal was one of his best issues. He blasted out ‘Keep the Canal’ materials all across the country.

People on the grassroots right found themselves inundated by letters from overlapping interest groups appearing to duplicate and water down one another’s efforts. Yet, Viguerie was deploying an intentional strategy by sharing mailing lists from group to group, enabling him to reach Americans who prioritized a plethora of organizations and issues indicating that they would be sympathetic to the fight against ceding the canal.

Reagan also saw opposition to the treaties as a way to stay in the public eye and build support for another run at the presidency. His Committee for the Republic and his top political advisor John Sears denounced Carter’s treaty preparations, proclaiming “The one man who can rally overwhelming public opinion against these disastrous actions is Ronald Reagan.”

Read More: Jimmy Carter, the 39th U.S. President, Has Died at 100

Opposing the treaties became non-negotiable for any politician or group looking for conservative support.

As the Senate geared up to debate ratification, a self-proclaimed Truth Squad consisting of Kansas Senator Robert Dole, Illinois Representative Philip M. Crane, California Representative John Rousselot, and other congressional leaders geared up to torpedo the treaties. The grassroots push flooded Senators with a deluge of “Keep the Canal” letters and petitions.

Despite these efforts, however, the Senate ratified the treaties by a 68-32 margin. In the end, Democratic control of Congress made stopping the treaties impossible, especially given the lingering strength of Ford’s more moderate wing of the GOP.

Yet, the strong grassroots pressure forced Senate Minority Leader Howard Baker, who played an instrumental role in securing enough bipartisan support to ratify the treaties, to reverse course during his campaign for the 1980 Republican presidential nomination. Revealing the continued potency of the issue, Reagan’s campaign was inundated with letters begging him to abrogate the treaties and maintain American power abroad should he be elected.

In 2025, the right looks significantly different than it did in the 1970s. One thing that remains the same, however, is the fractious nature of Trump’s coalition. Tensions over the debt ceiling and spending have already prompted Trump to call for a primary challenge to Texas Representative Chip Roy. These divisions threaten to create headaches for Trump.

Many in Trump’s orbit have brushed aside his Canal threats as a mere negotiation tactic. Yet, once again, the Panama Canal may prove to be an area that can bring the diverse MAGA movement together. As in the 1970s, demands to restore a supposed decline of American power abroad could amplify the populist nationalism undergirding the seemingly paradoxical facets of Trump’s America First policies and at least temporarily pave over the Republican schisms threatening to derail his agenda.

Aaron Coy Moulton is associate professor of Latin American history at Stephen F. Austin State University and on a research fellowship from the Center for History and Culture of Southeast Texas and the Upper Gulf Coast with Lamar University.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.