Editor’s note: The following blog post originally appeared on Levi Gundert’s Substack page.

Gartner estimates that 5% of large enterprises currently maintain cyber-fraud fusion centers, which is expected to jump to 20% by 2028. “Fusion” sounds high speed, but bringing together multiple teams for a shared mission can slow down operations if not managed effectively. A traditional SOC masquerading as a fusion center with little more than pew pew maps (not to diminish their effectiveness with executives) defeats the purpose. A successful fusion center removes data silos and works across traditionally divided teams (e.g., Incident Response, Cyber Threat Intelligence, Fraud) to improve threat actor campaign analysis and reduce losses. Cyber-fraud fusion centers improve communication and collaboration through organizational (and perhaps physical) proximity, leading to better fraud loss reduction outcomes.

Introduction

Before exposing cyber-fraud data flows and focused loss mitigation examples, a few words about the problem and a prerequisite for success. In January, Nasdaq released a remarkable report that quantified illicit money movement, including “losses from fraud scams and bank fraud schemes accounted for nearly $500 billion globally in 2023.” That number is a significant enticement for threat actors to continue with successful tactics while also investing in new fraud innovations.

A thriving fusion center requires a leader with vision and experience (in cyber defense operations and fraud) and the mandate authority (“juice”) to remove traditional enterprise barriers (organizational empire building, information gatekeeping, vendor firewalling, etc.).

Improved Data-Driven Workflows

The fusion concept is vital in this fraud context because CTI analysts generally focus on identifying malicious fraud communities and associated TTPs (tools, tactics, procedures). Fraud analysts, conversely, are concerned with creating fraud analytics toward enhanced remediation. In traditional organizations, the CTI and fraud teams sit in separate departments and are constrained by politically driven data silos. Optimized information workflows for maximum fraud impact remain elusive. When implemented correctly, cyber-fraud fusion centers remove perverse incentives and enable a unified team to make the organization more effective.

In each of these examples, we’ll examine how CTI can enrich fraud investigations and help shift from a reactive to a proactive posture (though overused, this “proactive” notion is appropriate here).

Example Alpha – Payment Cards

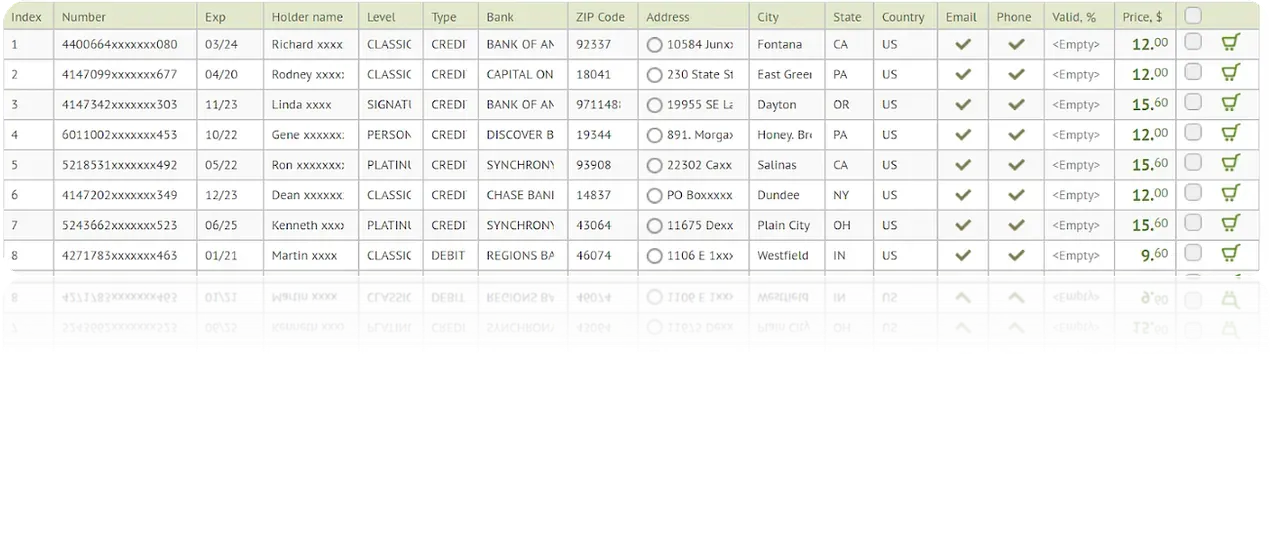

A straightforward example includes payment card fraud (“card present – CP” and “card not present – CNP”). CTI teams will identify and collect in criminal forums, marketplaces, and other communities where stolen full or partial payment card details are advertised and sold.

An example database of stolen payment cards.

Stolen payment card services branding.

A fraud team workflow may include:

- Identify at-risk cards and monitor the associated portfolio exposure in real time

- Track fraud mitigation turnaround time as a primary KPI (key performance indicator).

- Reduce criminal interest in specific payment card portfolios

- Decrease false-positive rates in risk-scoring solutions

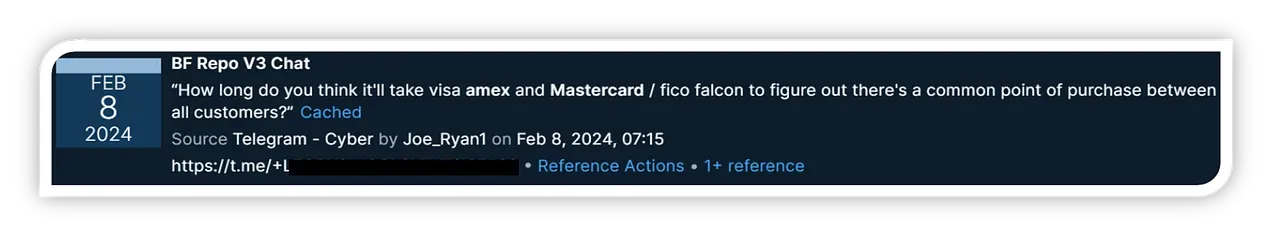

- Conduct CPP (common point of purchase) analysis before chargeback data arrives

A Telegram-sourced conversation – courtesy of Recorded Future – regarding defeating fraud detection mechanisms.

Commonly used fraud controls include KYC (Know Your Customer) rules, test transaction monitoring (a strong fraud precursor signal), CAMS (Compromised Account Management Systems) alerts, and CPP (common point of purchase) analysis. The issue is that all of these controls are reactive. CTI, when done well, changes the paradigm in that intelligence is proactively driving fraud prevention, reducing the efficacy of fraudster tactics, and traditional fraud controls become deprecated as a first line of defense.

Example Beta – PII & ATO

Recorded Future AI insights and cashout service branding.

Some organizations (e.g., retailers) may not issue payment cards, but experience heavy fraud losses due to the unauthorized access of personally identifiable information (in the U.S., valuable PII for fraud may include: physical address, email address, date of birth, social security number, phone number, mother’s maiden name, etc.), which is subsequently used to tailor social engineering attacks that lead to account takeover (ATO). This is also true for banks. A stolen payment card may be quickly identified and re-issued, but the associated stolen PII may lead to fraud losses through call center social engineering and/or online channel security bypass. The unauthorized access to online accounts may lead to unauthorized money movement to mules who specialize in maintaining bank accounts to receive stolen funds and “cash out.”

In another life, working with banks, we engaged fraudsters online to identify previously dormant cash-out accounts. At the time, even if a victim wasn’t participating in online account access, fraudsters would enroll victims using stolen PII and create the necessary authentication details (username, password, etc.). Out of convenience, all compromised accounts contained the same password.

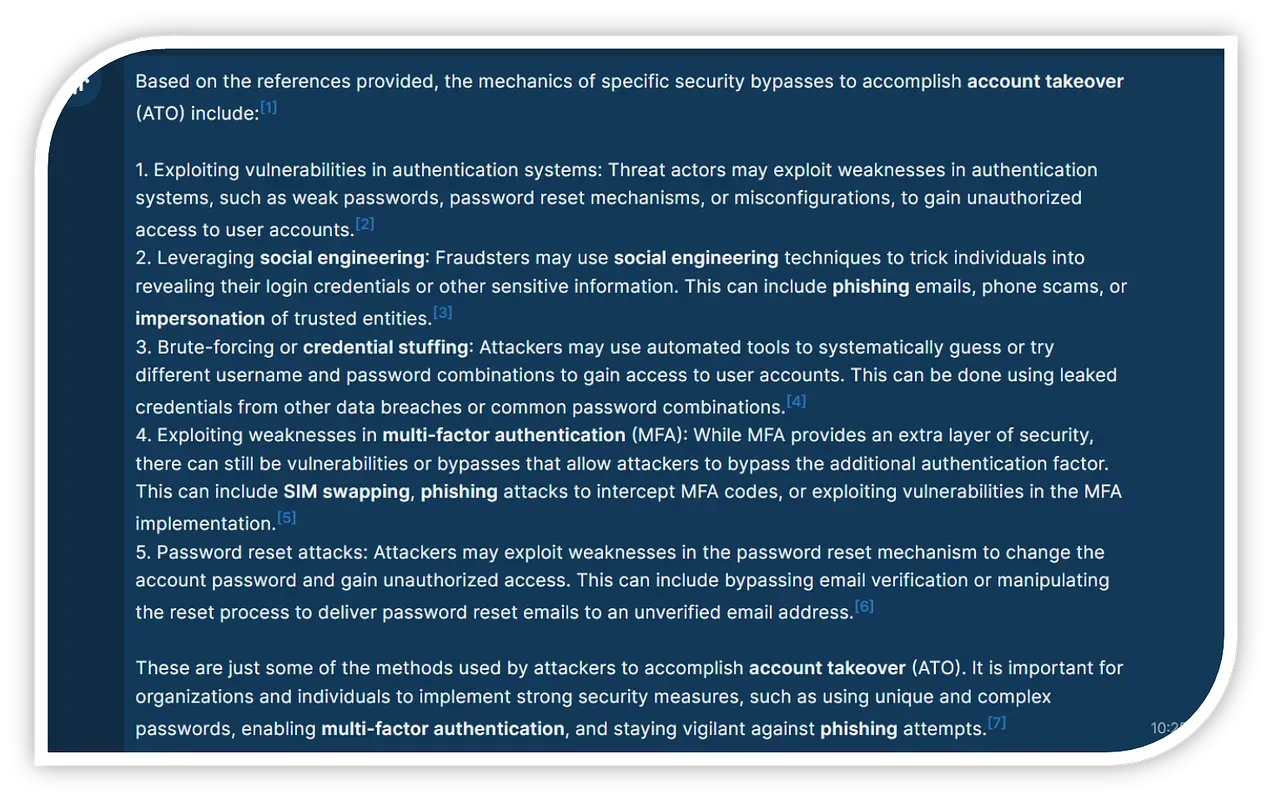

ATO mechanisms include MFA prompt fatigue (the victim is tired of selecting “no” and seeing a dialogue prompt reappear), credential stuffing / brute forcing, social engineering, SIM swapping, password resets, etc. Naturally, GenAI is reducing the time to prepare and deliver while increasing the quality of social engineering campaigns. ATO and associated cashout techniques are constantly changing. Fraud professionals collaborating with CTI will help identify the right threat actors for engagement to further intelligence objectives that lead to fraud control improvements.

An infostealer coterie – Lumma, Vidar, Raccoon, Redline.

Additionally, infostealers (a specific label for a malware genus focused on extracting all victim PII and more from web browsers) have stolen billions of victim credentials, cookie values, and more. This data treasure trove enables fraudsters to use valid credentials and quickly achieve ATO for both social engineering and direct money movement in financial services platforms.

Recorded Future AI Insights for ATO channels.

Focused Examples

Example Charlie – Magecart Compromised Merchants

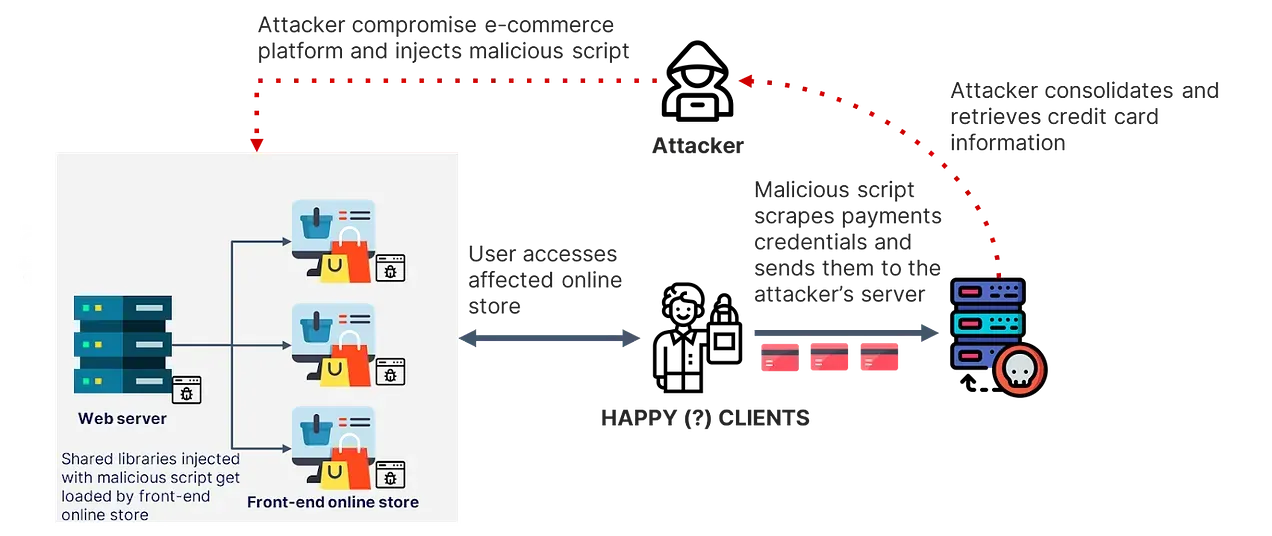

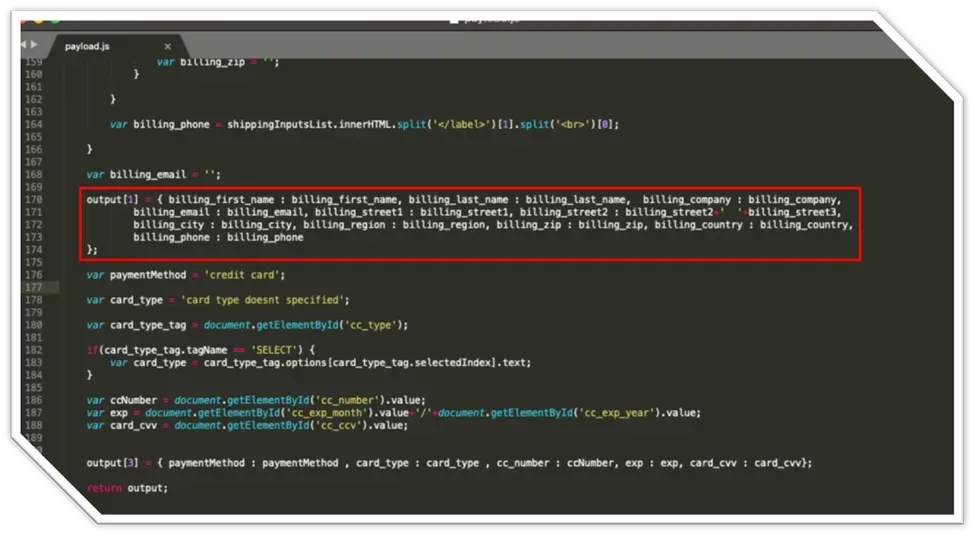

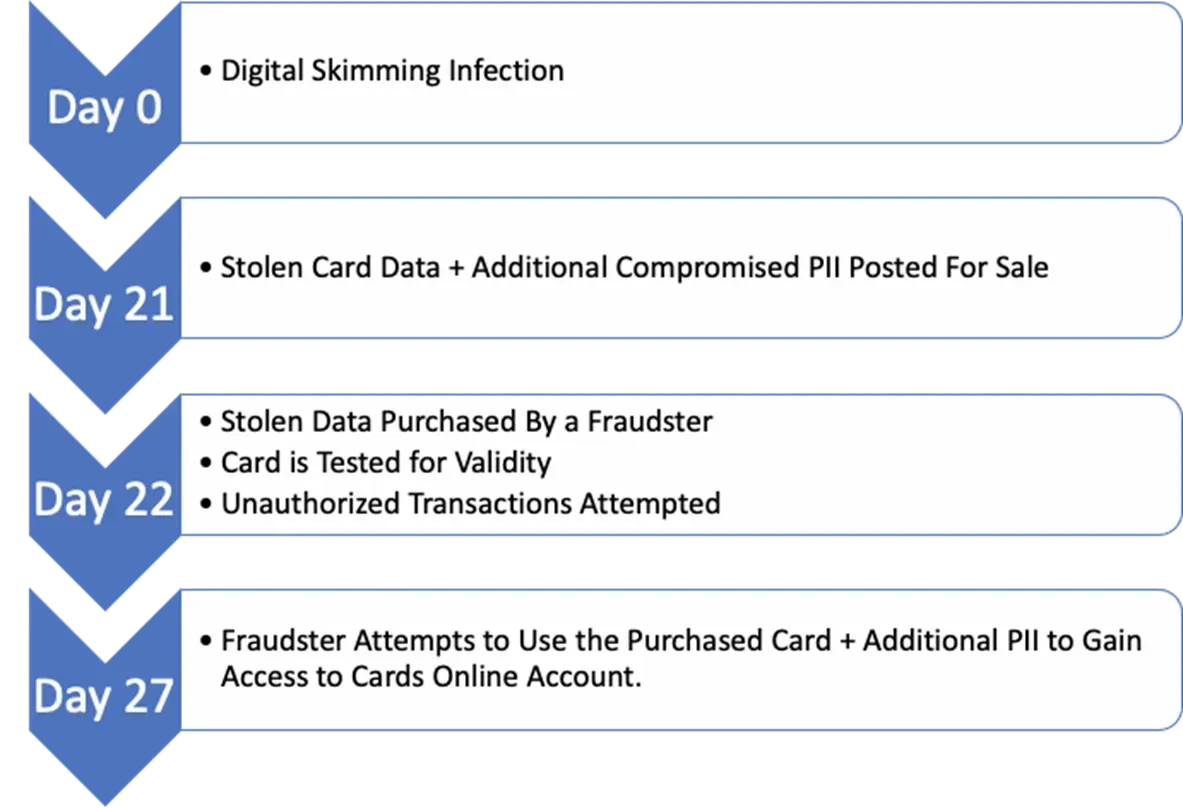

“Magecart” is the label for specific malicious scripts (code) loaded into vulnerable e-commerce platforms to skim payment card details during customer payment. As previously mentioned, Magecart victims may have to consider more than just replacing their payment cards in certain shopping contexts.

A Magecart data flow diagram.

Details of e-skimmer code illustrating customer fields for exfiltration.

Proactive Magecart intelligence is important for e-commerce retailers and financial services companies advising and alerting retailers, specifically small and medium-sized companies with fewer resources to invest in security. Magecart TTP evolutions require corresponding agile detections. Several historical Magecart operating changes observed by Recorded Future’s Payment Fraud Intelligence (PFI) team include:

- Using Google Tag Manager

- Payment card data exfiltration to Telegram

- Hiding malicious scripts within SVG elements and using stenography

- Using compromised websites as proxies to distribute malicious payloads

Fraud teams can track the monetization paths and timelines post-compromise, while CTI teams can actively help identify magecart-victimized merchants before the monetization clock starts.

Example Delta – Scam Merchants

A verified scam retail website.

A comprehensive strategy to uncover scam merchants involves open-source research, collaboration with industry partners, and advanced data analysis. Organizations can source suspicious websites by monitoring social media advertisements, reviewing domain registration details, and investigating patterns in merchant account behavior. Further validation of potential scam websites can be achieved by correlating domain data with cards exposed on the dark web, identifying common patterns across fraudulent sites, and leveraging consumer reports of suspicious activity. By integrating these insights, organizations can avoid emerging threats and effectively mitigate payment fraud risks.

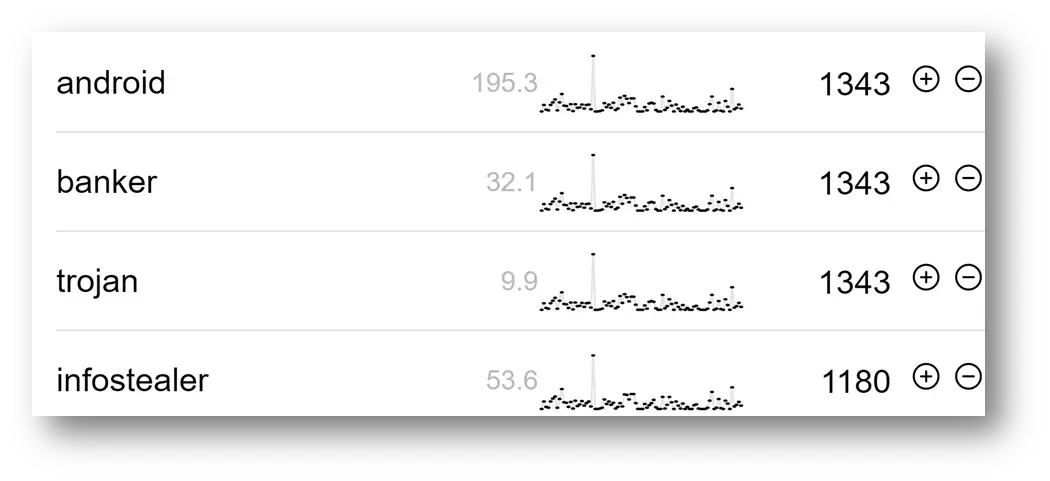

Example Echo – Android Banking Trojans

Mobile malware is particularly pernicious in retail banking geographies outside of North America. Recorded Future observes thousands of malicious files with anti-virus signature names like Hydra, Hook, Sova, and more every quarter. For example, Thailand has been alerting citizens to the dangers of installing unverified Android applications, which could drain their bank accounts. While mobile malware generally contains many features (e.g., accessing location services, camera snooping, reading/sending SMS, etc.) that achieve device takeover (DTO), creating man-in-the-browser (MitB) capabilities during online banking sessions is the most impactful for fraud losses because traditional multi-factor authentication (MFA) mechanisms become less effective when all communications channels can be intercepted and manipulated, leading to account takeover (ATO).

Again, while financial services fraud teams and government investigators have digital exhaust to follow after victimization, CTI teams should create alerts and dissect new mobile malware TTPs to better educate the banking and online shopping public (and pursue attribution).

A sample of malware tags derived from Hatching Triage.

Additionally, real-time notification of new mobile malware samples with associated meta-data improves bank prevention/detection systems via atomic indicators (e.g., user-agent strings, IP addresses, etc.) and internal log correlation.

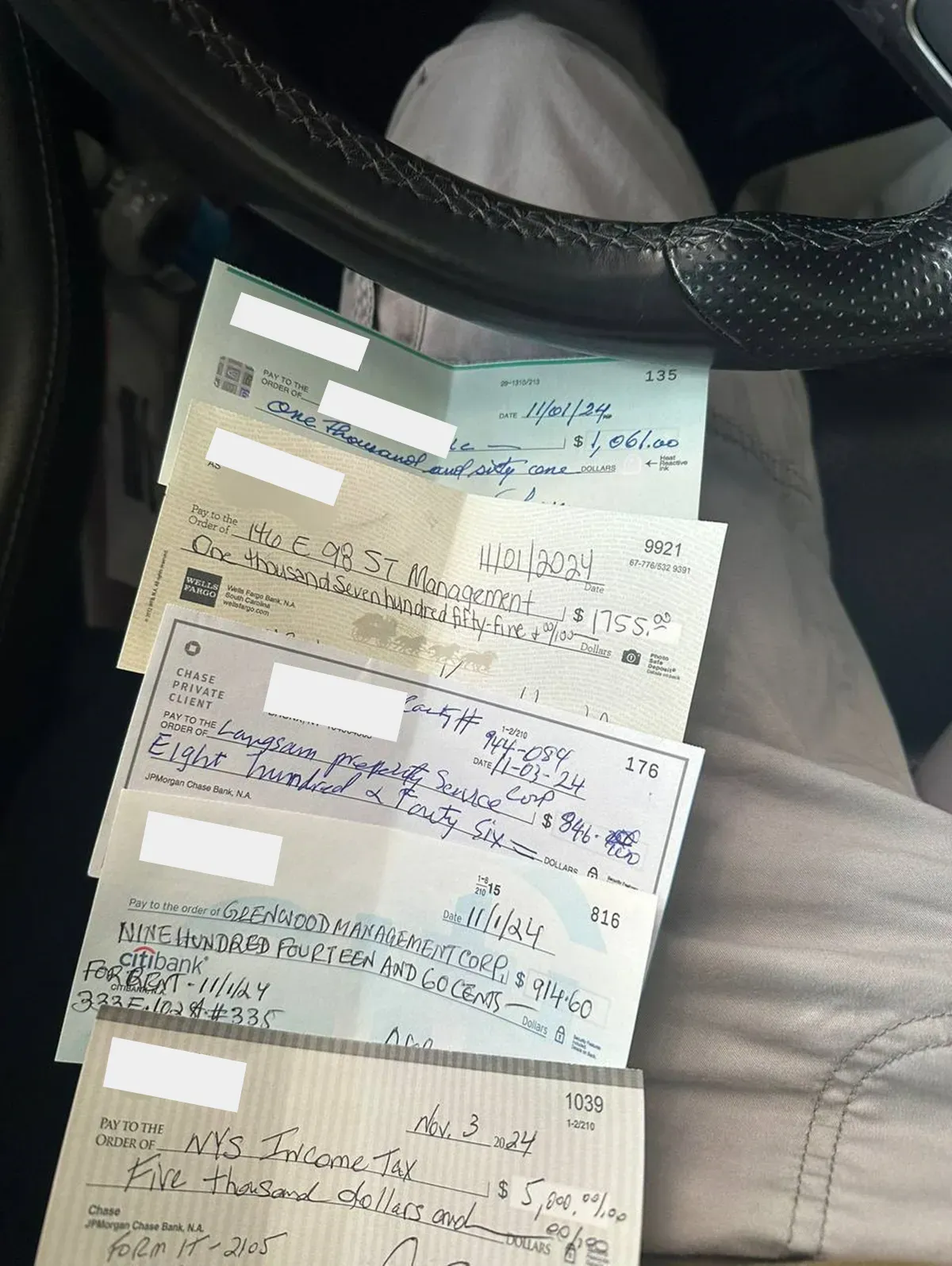

Example Foxtrot – Stolen Checks

Physical (paper) checks are a relic of the banking system employed primarily in North America. Because these documents contain a routing and account number, they are still heavily used in fraud. Older generations are vulnerable as they may prefer checks for a reliable payment mechanism over other fintech options, which are perceived as potentially less reliable.

The CTI opportunity is to use optical character recognition (OCR) for check image recognition in online criminal communities and proactively work with a fraud team to neutralize the inevitable fraud before victims report it.

Stolen checks are shared in an online criminal community.

Conclusion

Strong leadership, clear expectations, and success measures are prerequisites for cyber-fraud fusion centers. By better understanding these complimentary workflows in:

- Payment card theft

- E-commerce skimming

- Physical checks

- Mobile malware

- Account takeover (ATO) and cash-out

- Scam merchants

fraud and CTI resources (human or machine) can better architect and deliver improved organizational fraud loss value.

Thank you to Recorded Future’s Payment Fraud Intelligence (PFI) team and Insikt Group for their foundational work in enabling this blog and their continued excellence in malicious cyber fraud campaign analysis.