Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

These days, if you see someone with their head bowed, you’re much more likely observing them staring into their phone than in prayer. But from digital rituals to the promises of abundance from Silicon Valley elites, has technology become the world’s most powerful religion? What kinds of promises of salvation and abundance are its leaders making? And how can thinking about technology in this way help us generate ways to reform our approach to it, particularly if we aim to restore humanist principles?

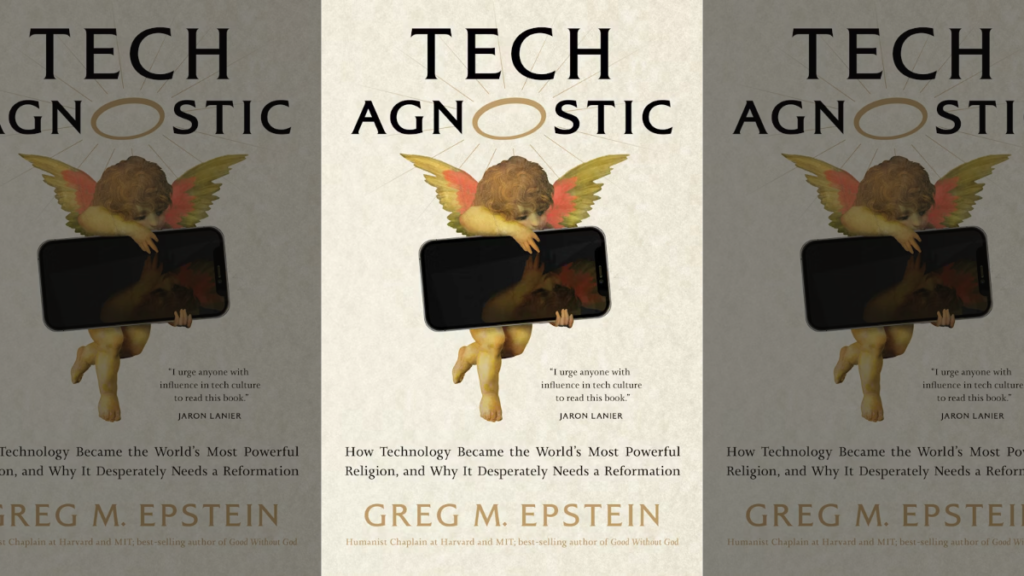

Today’s guest is Greg Epstein, who drew on lessons from his vocation as a humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT to write a new book, just out from MIT Press, called Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation. The book has received excellent reviews and coverage in outlets such as The Guardian, The Boston Globe, POLITICO’s tech podcast, Fast Politics, Closer to Truth, and The Ink, and was listed as a must-read by the Next Big Idea Club. I caught up with him to discuss its key ideas.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

Greg Epstein:

My name is Greg Epstein. I am the humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT, chaplain for the non-religious in those contexts, work on interfaith issues as well, and I am the author of a new book called Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation.

Justin Hendrix:

Greg, I’m so pleased to speak to you again and to have the opportunity to talk about this book. We’re talking about it in a new political context in the United States. I’m speaking to you on the morning of November 8th. Of course, Tuesday’s election was a definitive outcome, and I think for many of my listeners, they’re probably in a period of sense-making, trying to sort out what that means and trying to think about what the world might look like in January and beyond.

Towards the end of your book, you talk about the idea of a future worth conceiving. You write, “We are uncertain about the future of our climate. We are uncertain how to treat and connect with one another given unprecedented levels of border crossing and geographic mobility, not to mention racial, ethnic, and religious intermingling. We are uncertain whether centuries-long experiments in democracy can succeed or even continue as all our uncertainty seems to continually strengthen the hands of authoritarian leaders who prey on our weakness and doubt, asserting that they alone know the way. We are uncertain about what to believe as the old gods seem to be dead or dying. We’re also uncertain about our technological future, and in a tautological feedback loop, our technological future makes us ever more and more uncertain.” I feel like that sums up a little bit of how I’m feeling this week, and I wonder how you’ve been interpreting these events both through the ideas you explored in this book and personally.

Greg Epstein:

Thank you, Justin. I had not heard that piece of my book quoted back to me yet on this book tour that I’ve been starting the past week or two. And I’d forgotten that I’d written it in just those words because I was looking at a different section of the book the other day for where I had predicted this outcome and I didn’t quite find it there, and I realized, oh, yeah, that’s where I was really thinking about what this day or this week, these weeks might be like. But yeah, I would even add that people are not just processing right now, but grieving. When we experience loss, which can include the loss of a loved one, but it can also include loss of safety, loss of security, loss of hope, loss of opportunity, and when those kinds of losses, the non-immediate death sorts of losses are particularly strong, strongly felt, it’s not only natural but actually important to go through a period of grief.

And people nowadays, I think, are familiar with that language, but I think they don’t even necessarily know what it means to grieve. I don’t believe that any of this is meant to be, but I think part of what we’re meant to do today may be to process some grief for the sort of tech communities that might be following your work, your very important work, who are what I call some of the heretics, the apostates, the humanists in what I describe as a new tech religion. The people who exist on the periphery of that religion, some of whom are in important or even powerful roles, others are in more critical roles, journalists and such. But many, if not all of whom feel that they’re somehow of this new and incredibly powerful, even more powerful today realm that we call Silicon Valley, and I call the Silicon Valley Religion.

And you’re in it, you’re of it, but not quite. You situate yourself emotionally, mentally, practically, maybe on the outskirts of it, marooned perhaps from feeling that you can just identify with its basest instincts and making perhaps part of your life about critiquing what I call the religion and trying to reform it. So if that is some of the audience that’s listening to us right now, then I think those people are probably experiencing real grief and probably need to let themselves do So for a little while.

Justin Hendrix:

Let’s talk a little more about your hypothesis, and you’ve just got into it very much that technology is a new religion, a global religion, one that is as diverse in who is part of it, who opposes it, who is regarded as a reformer, who is regarded as heretic, as you say, we’ve got apostates, we’ve got heretics. You talk about infidels, heathens, unbelievers. You talk about the Luddites, the whistleblowers, all of the various, I suppose, flora and fauna in this ecosystem that are challenging and in some cases advancing this religion. How would you, for the listener, describe the basics of this religion?

Greg Epstein:

First of all, because we’re talking to smart people right now who can see through anything that’s like puffery or just for sensationalistic purposes that I think the question to start with would be, am I literally saying that what we call tech now is the world’s biggest, most powerful religion, or is it just a really long extended annoying 300-page metaphor? And the answer is yes, it is both. I get it. It’s not a literal religion in the sense that, for example, there’s this thing called Way of the Future, which I talk about a little bit in chapter one, which is a literal ‘sign the paperwork with the federal government’ to make it a religion, worship of AI as a new god. That was started by a guy named Anthony Levandowski, who made $100 million-plus as a self-driving car engineer, was convicted of stealing trade secrets, pardoned by Donald Trump, blah, blah, blah.

He literally says, ‘This is a religion. AI is the new God. It’s going to come online very soon, and it will be very angry at us if we don’t start worshiping it soon.’ I’m not talking about the whole of Silicon Valley in the sense that Levandowski is talking about it. Of course not. He’s a sort of ridiculous character to me, but I wish he were more of an isolated incident. In fact, there are so many examples that are very similar to him from mainstream, influential, important, and often very wealthy people. But what I would say to the listener is, take a ride with me here on this journey where we try viewing tech as something other than what would we tend to call it? An industry. We use that phrase algorithmically, the tech industry, but it doesn’t make sense anymore because there’s no industry in the world of any consequence that’s not a tech industry. I even spoke to an interviewer recently, and I said, “Basket weaving, maybe.” And she said, “Oh, no, I know about basket weaving. Basket weaving is a tech industry now too.” Okay.

There’s no industry anymore that’s not a tech industry of any size or consequence. And so what is tech in our lives today if it’s not an industry, if it’s beyond that, if it’s so dominant in our lives, we interact with it from the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep? And in so many ways we’re interacting with tech even as we sleep now. It’s eaten every aspect of our economy. The real religion, you might say, is capitalism, but tech has eaten all of capitalism as well. There’s no form of capitalism left that isn’t technological or Silicon Valley-style capitalism. So what is it in our lives? And I’m saying take this ride with me where we look at it as I started to do about six years ago as a religion.

And if you do that, I think you might gain a greater sense of understanding of the role that tech is playing in our lives now and in the role that you want to assign to tech in your own life. Because there may be religious people listening to this, but you’re not religious in every way. Even if you are a deeply religious believer and I as an atheist chaplain, I welcome you, I respect you, and I can learn from you. But you don’t give credence to every religious claim that is made. You don’t worship every god, and so take the part of you that’s skeptical about some of the gods and some of the religions and apply it to this and decide how you want to relate to this particular religion.

Justin Hendrix:

Along those lines, there are a lot of ideas that flow through here that folks will recognize when we talk about religions, questions around salvation and questions around promises of abundance, questions around apocalypse, and, I suppose, forms of damnation. What do you think? Let’s go through a couple of those. When it comes to abundance and salvation or maybe enlightenment, which are often kind of goals or promises of major religions, where does tech fit?

Greg Epstein:

Abundance. Sam Altman talks about, he uses the phrase, “Abundance is our birthright.” So here is a tech CEO who is currently even after the book that I wrote, has been going around requesting to say the least, hat in hand, maybe 5 to $7 trillion to place data centers, data centers that have or use the power of nuclear power plants all across this country and beyond in order to have us interact with chatbots, generative AI and other related technologies to an exponentially greater extent than we already do. And it’s already become quite a bit of our lives. The abundance that Altman is looking at is what? The claim is that we’ll all have abundance, which is the kind of claim that you hear in a lot of religions and that you should hear the echo from “abundance is or birthright” to “be fruitful and multiply.” Be fruitful and multiply your technologies.

But the abundance that is really birthrighted in this equation is often to the high priests, to the demigods, to the deities themselves. They really are getting quite a bit of abundance right now, and so in that sense, their prophecy isn’t wrong. But for the rest of us, one could say as some have, my friend Steven Pinker, perhaps among others, you have to understand, we’re making progress. We’ve been going uphill technologically and scientifically; we’ve made so much progress. This is a better time than any other time before, and it’s true. Abundantly, I would admit that there’s not a particular time in history that I would want to go back to fully for sure. But there’s this idea that you can be on your way up in a roller coaster, and the first 30 seconds to a minute of the roller coaster, you’re going up, but that doesn’t necessarily have decisive implications for what’s going to happen in the next 20 to 30 seconds.

So that’s my approach to abundance, which is, it’s a great word to give you a sense of the Silicon Valley ideology, especially in its latest iteration with somebody like a Sam Altman who really has no trouble using religious language, talking about his creations as miraculous, even as he sits in churches like Harvard’s Memorial Church to discuss them.

Salvation. Humans are always looking for solutions because human life is precarious. We are constantly at risk of loss, of death, of sickness, et cetera. Of course, it’s natural to think, help me, save me. Neil Postman, the great media critic, and tech critic, would point out that, unlike prayers, planes fly, penicillin works. He pointed out way before me in his book, Technopoly in 1992, when he was worried about the role his fax machine was playing in his life. That technology can look like religion, with that caveat that some of this stuff really works, but is it salvation? Is it not just a solution or a tool, but the solution, the tool? That is where I think religious marketing or religious homiletics, religious preaching often breaks down it.

If you’re like me and you’re fascinated by religion, you know that it’s a very diverse phenomenon, and there are all sorts of good preachers out there. They may be Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Zoroastrian, whatever. My Zoroastrian chaplain friend at Harvard and MIT is actually one of my very favorite religious people, and he even gets a little bit of airtime in chapter seven of this book. But there are all sorts of good preaching that help us to at times be more generous because it’s hard to be generous at times, more thoughtful because it’s hard to be thoughtful, more community-minded because it’s hard sometimes to be community-minded. But when religion breaks down as it so often does, unfortunately, when it says, “This isn’t just a lesson, this is the lesson, and you must follow me to the very end of what I’m going to preach to you because only I have the way to paradise. And if you don’t follow me, you will go to the other place, and it will be hot as hell there.”

Actually, too much of Silicon Valley Tech is really presenting itself not just as a tool or a solution but as a salvific solution. Ray Kurzweil talks about the singularity in precisely these terms. He says that in the next, I don’t know, 10, 20 years or so, not next month, never next month, because next month we could quantify his argument, we can track his progress. Has to be just enough out of sight that we can’t quite measure what he’s talking about, but he says that we’re all going to upload ourselves into this cloud to the extent that we’ll essentially end death as we know it. This is why he takes his 200 pills or whatever every day so that he can stave off aging just long enough to upload himself. And he says that, therefore, life will be made meaningful. And I got to ask him recently as I was getting ready for the book to come out, “Mr. Kurzweil, doesn’t that sort of fly in the face of religious and ethical teachings from both secular and non-religious teachings throughout history? Like life hasn’t been meaningful up until now?”

And he looked at me and he thought about it, and he said, “Maybe life has been somewhat meaningful up now.” But that’s the level … Kurzweil was perhaps leading the charge for Google’s Gemini with this exact idea in mind. Blake Lemoine told me, for those who know that name, Blake Lemoine told me that Kurzweil designed Gemini to resurrect his dead father. So if tech people want me to stop saying that this is a religion, they really need to stop acting so religiously.

Justin Hendrix:

So let’s get into the flip side of that. So there’s the premise of heaven, there’s the premise of enlightenment, the premise of salvation, the cloud that we’ll all find great meaning in. You also talk about apocalypse and versions of apocalypse that people see. Perhaps when that roller coaster takes its dip, or in some cases individuals that you’ve spoken to who believe the apocalypse is very much here. You point to someone who’s been on this podcast a couple of times in the past, Chris Gilliard. Some folks will have known him as “Hypervisible” on Twitter and hopefully now Bluesky as well.

Greg Epstein:

He’s great on Bluesky again. It’s a relief to see him doing his thing again.

Justin Hendrix:

You spent some time with Chris in Detroit, features prominently in this book, and you come back to this idea that he shared with you, I’m paraphrasing, “The tech apocalypse is already here. It’s just unevenly distributed.” What is this alternative vision that others are suggesting?

Greg Epstein:

Yeah, so first of all, one of the theological or doctrinal, religious doctrinal points that I want to help people to understand as my framing here is that religions make these claims about heavens and hells because that is, it’s really … At times, it’s to hope, inspire hope, and help people. But it’s also true that these are really motivational claims. People are afraid to gamble their lives if this might be true, and so they fear of missing out on heaven or fear of not missing out on hell, they get behind theologies that they might otherwise be critical of. You have this in the sense of the salvation ideologies that I was just mentioning. There are so many other examples that I give in the book and can give otherwise.

But then there’s this sense of the tech apocalypse, the idea that we’re told by the effective altruist movement and other doomers, including now we’ve got a Nobel laureate doomer in Geoffrey Hinton, that there’s perhaps, according to the 80,000 hours website, this sort of career advising, life advising website for the effective altruist movement that we’re told, there’s a 10% chance that runaway AI, unaligned AI will wipe out all of humanity in this century. And what’s the utility of an argument like that?

I would say that other religious preaching about hell, it’s tremendously motivating. If I know how greatly at risk we are, and of course, we’re told on that same site, it’s a book by Toby Ord, an EA philosopher, The Precipice. If I’m told that we’re on the precipice and that the person who’s telling me so can and only can, only they can help me avoid that precipice, then why shouldn’t I follow them wherever they want to lead me? I was really curious about visions like that. Like, hey, I’m an atheist when it comes to traditional religion, but I’m only an agnostic when it comes to this tech religion. I know that a lot of these technologies really are a power greater or at least higher than myself, not necessarily greater morally, but certainly more powerful than me or than many of us. And I don’t know which tech prophecies are going to turn out to be true and which ones aren’t. I have no way exactly of seeing into the future, although maybe we’ll get into it later. I have certainly have thoughts.

And so I wanted to talk to somebody like a Chris Gilliard who talks about how so many tech leaders are like Silicon Valley supervillains, comic book supervillains, and his tweets about that in the age when somebody like him felt comfortable or safe on Twitter were some of the best viral content I ever saw in my life. It was just so brilliant the way that he would use a comic book supervillain metaphor to break down the way that Silicon Valley leaders were behaving.

And so I said, “What do you think? What do you make Chris of this idea in a city like yours in Detroit, where there’s this thing called the Green Light Project?” Which is thousands of cameras surveilling people like him all across the city so that white suburbanites who fled the city after the uprisings of the 1960s can feel safe going there for commerce, going there for sports and entertainment, and then going back to their safe havens without the fear that some crime might happen to them but without any effort whatsoever to rehabilitate that city to make it a better place to live for the people who are there. Which is, of course, what would motivate most, if not all, of the crime that’s happening there anyway, if there is a crime, if and when there is a crime.

I said to him, “What do you make of this? It seems like there’s this apocalyptic reality right now already in parts of Detroit, but is it getting worse? Is Detroit an example of tech gone most wrong, tech gone most bad? Is it the kind of panopticon that more of us should look forward to if we’re not careful about restricting or recalibrating the development of these technologies, the way people can be disappeared if they’re activists in Hong Kong or other parts of China and other parts of the world now? Is that what we have to look forward to?” And Chris, I’ll let people read the book, but the story is, first of all intense. He’s a privacy researcher. He’s intensely private. The only way I got him to let me come and spend two days with him, and he’s become a friend, I love the man. I really do. But he let me come when I was able to arrange a joint interview between him and myself and his all-time favorite comic book writer and artist, Jim Starlin. I’ll leave it there that some of that interview appears in the book.

But anyway, he takes me around Detroit and shows me both the good history of technology there and the very dark foreboding history of technology, including current events. And as you say at the end, he tells me, “The tech apocalypse is already here, Greg. It’s just unevenly distributed.” And I guess where I would finish this thought, I’ll let readers see what my conclusions are and his conclusions are about how apocalyptic our current tech actually is. But I’ll just say in recent days, we saw a little bit more redistribution of the apocalypse, and that is perhaps what those of us who are grieving in mid-November are feeling.

Justin Hendrix:

I think partly what we’re talking about a bit is a figure like Elon Musk who has just been elevated in an extraordinary way politically in the United States. I had just read moments before we got onto this podcast conversation that in a conversation that President-elect Donald Trump was having today with Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Elon Musk was invited to be on the line and having a conversation about the affairs there and Musk’s role and Starlink and things of that sort. It’s extraordinary to think that in the days following this election already, we’re beginning to see Musk as a partner to the soon-to-be President again of the United States. He, in particular, is an incredibly powerful person, forecast to be a trillionaire within a couple of three years, not just active politically here in the United States, but active all over the world and very much has this vision of the necessity of technology to reshape the planet and of course to reshape our ability to get beyond this planet. How are you thinking about him in the context of this book?

Greg Epstein:

Yeah, it does strike me that people like Musk are playing a kind of scaled-up role in what’s going to emerge as the Trump administration, that megachurch preachers used to play in the roles of other Republican politicians. Reagan, for example, famously rode to power on the wave of a newly politically active conservative coalition that included preachers like Ralph Reed and Jerry Falwell, those sorts of folks. And there’s still that, by the way, in today’s Republican Party, but they’ve been joined, and I would say even superseded by these mighty tech preachers and prophets.

And your listeners probably know a lot about Musk already. I don’t know that they need me to opine at length about him, but I’ll just say that one of the things that strikes me about him is Elon Musk doesn’t really understand healthy human relationships or healthy human interaction. He and people like him are not concerned that we would spend more and more of our time relating to tech rather than relating to one another. Because throughout his life, his attempts to relate to other human beings and to himself have often been thwarted, have produced a kind of learned helplessness that doesn’t show up for him, or to the opposite, isn’t in his interactions with technology. So for him interacting with technology and solving every problem with technology really is a working strategy, a working approach to life, because it’s what he’s known.

But for the rest of us, that may not be the case, and we may not want to live in Elon Musk’s world where Mars is the solution rather than the solution being to make this world better. Where AI is the solution, the godlike power, rather than improving our ability to understand and connect with our own emotional intelligence. That’s just not on the menu of options for Musk. And I think this really struck me. At one point, we were having a conversation on the Tech Policy Press chat, Justin, and we were talking, I think at the time, it wasn’t even about Musk. It was about, if I recall correctly, it was the effect of altruists and the long termists and the desire to create this sort of magical tech future in the long-term where there’ll be trillions of digital beings uploaded into the cloud powered by distant stars. And forget worrying about things like climate or racism or gender oppression here on Earth. Get to the stars.

And in fact, Jack Dorsey says just that when he’s turning the keys of Twitter over to Musk. He says, ‘Elon is the singular solution … in which I trust to take humanity to the stars.’ And Danielle Citron weighed in about this at the time, and this is on page 86 of my book, Tech Agnostic, where she ultimately goes on to tell me, she says that, by the way, Danielle Citron is a MacArthur genius fellow and Singers professor of law at the University of Virginia Law School, and she describes her work as on how people can “lose their way behind screens because they don’t see the people whom they hurt.”

She goes on to say to me that to build a society for future cyborgs as one’s goal suggests that these folks, people like Musk, people like Sam Bankman-Fried, and others, don’t have real flesh and blood relationships where we see each other in the way that Martin Buber described. Martin Buber is an existentialist Jewish philosopher from the early 20th century who talked about having a deeper connection between human beings, where we see each other not just as objects but as deeply human in all of the senses of that word, beings that we can love and be loved by. And we lose the plot, we lose that plot too often when we muskify our world, and that is exactly what I think Donald Trump is looking forward to doing.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to come back to this idea of the tech kind of CEOs or the tech influencers replacing the sort of evangelical movement as the most important kind of channel to organize people and perhaps to raise money in politics, particularly on the right, although it’s true, certainly on the left as well. I don’t know. It makes me think of a couple of different things that have been grinding around in my head for a few years.

One is that when you think of, you mentioned megachurches, and I think about Erica Robles-Anderson and the work that she’s done to look at those as a phenomenon, as a media phenomenon, as a channel to reach large numbers of people and to coordinate their activities. And then to the extent that we think about tech firms and we think about digital communications as a means to coordinate collective behavior or to organize humans or motivate or push them in a certain direction. But it seems to be that these things are all related somewhat. I think of tech as being software for making people behave in certain ways, do certain things, and potentially accomplish certain things together. But I don’t know, these days it seems less about empowering individuals and more about creating structures for control.

Greg Epstein:

Yeah, when you reach a certain point with religion, there are places in religion and religious communities where there’s a lot of very deep empowering of individuals going on, and I want to make that again very clear. I’m an atheist professionally, but I’m also a chaplain. I work in interfaith contexts, I’ve worked in interfaith leadership roles, and I think there’s a great value to a lot of the communities that I don’t agree with theologically, but I agree with so much socially, not everything but so much, and there is that individual empowerment. But when you really want to scale a religion, a lot of the inner individual empowerment ends up needing to go because in order to really empower individuals, it turns out one of the things that you’d want them to do is think for themselves. You can’t really individually empower people if they have turned over their critical thinking to somebody else, to some other institution. You’re going to need them if you really want them to solve problems, to be able to go to a place of deep reflection and thoughtfulness and to solve problems.

But again, if you’re trying to generate truly mass worship, you don’t want that so much. You want people who are willing to delegate their sense of what’s important and what’s worth doing to you. There’s so much power and money available in tech today. So much so that I would say the chief theological symbols of today’s tech religion in the way that you’ve got your crucifix for Christianity and your Star of David for Judaism and your crescent and your wheel of Dharma, et cetera, the chief symbols are really the hockey stick graph forever upwards, profits forever upwards, scale forever upwards, the user adoption forever upwards and the invisible hand of the market. Think about, that’s in chapter one, I explore that. Think about how religious that actually sounds. The idea is if you are a trillionaire and other people are hurting, that’s an amazing amount of labor that you can buy.

And Musk one thing about him, he’s nakedly putting it out there. He went out during this election cycle and literally tried to buy not only people’s votes, but even their activism. There was this lawsuit just a few days ago where women realized too late that Musk had sent them out and basically put them in harm’s way, left them isolated to go door knocking. They weren’t told until they were taken across state lines that they would have to knock hundreds, if not 1,000 or more doors for Donald Trump in order to get the money that Musk had promised them, which he really ultimately was very unwilling to pay. If you become a trillionaire, you can do that times how many? A billion? I don’t know. I hate to sound conspiracist here, but I would just say this.

If a weird traditional religion were influencing this many people, billion people, all of a sudden within just one generation, or if of a billion or more people we’re interacting all day every day with the altars and the churches and the messages of a new traditional religion that was asking them to support weird candidates like Donald Trump. I think we would know to be critically minded about that. But because this is secular technology and we associate such things with rationalism and thinking, science, progress, we treat it as normal.

Justin Hendrix:

Towards the end of this book, you suggest that there are some truths that are self-evident. You offer a kind of humanist perspective, what you call a kind of tech agnostic manifesto. These include some basic ideas. That if you adopt this worldview, that tech is perhaps a kind of religion that might help you in thinking through the agendas, the people who are centered, and what that means. You say, “Tech hierarchies need to be flattened, which requires recognize them as the product of a religious ideology and critiquing them accordingly.” You talk about tech rituals in our own lives and how we should relate to those, the tech apocalypse which we’ve already got onto. You say, “Honor the apostates, heretics and Cassandras among us. We need them more than ever.”

And you talk about the idea that the tech culture of the future should be shaped by humanists, spiritual practitioners and others brave enough to build an alternative. We’ve given voice to others at Tech Policy Press who have this perspective. I’m thinking of Fallon Wilson in particular who wrote a piece for us recently that took this sort of point of view. Where are you looking for inspiration these days as you think through how to answer these questions going forward? Who you’ve mentioned, of course, Chris, there are many other individuals in this book, of course, that you admire. But where in particular, where are you getting your dose of optimism from these days?

Greg Epstein:

First of all, I’ll say I really hope that the book will be useful to people who are trying to figure out an alternative perspective to allowing ourselves to just be dominated by tech. It’s not an anti-tech book. It’s not saying we shouldn’t have technology or we should smash all the computers. I wouldn’t know how to write that book. I can’t imagine anybody reasonable would, so I don’t want people to worry about that. I think it could be useful for one reason that I probably could have finished it two or three years ago if I hadn’t been so invested in deep storytelling. I try to tell in this book, in basically every single chapter, a story that you can’t quite get anywhere else about the life and the struggles of somebody who embodies not only how this has all become a religion but how to maybe resist the worst impulses of that religion without becoming anti-tech completely.

And people like Chris and Veena Dubal among others, were really willing to share Kate O’Neill, the Tech Humanist, among others, were really willing to share deeply painful experiences with me to get at that. And I would say a lot of the listeners of this podcast are probably the tech humanists, the apostates, the people who are really building an alternative. Many of them are women or people of color or both. In fact, the majority of the folks that I found to be the wisest on these issues were … It’s a very diverse group. There are white men like you and me who are also really working in very constructive ways, but a lot of people who have been marginalized because of their identities, who then are enmeshed in the world and how the tech world and how hierarchical it can be that it becomes easier for them in some ways to think about how to fight back.

And there’s a lot of storytelling about that that I think can actually be quite inspiring for readers who might find themselves thinking, “Okay, if that person, if a Payton Croskey or a Chris Gilliard or a Veena Dubal, et cetera, can push through and create an alternative perspective on technology that allows them to get past some of the really deep suffering that the tech world has caused them, then I can too.” That’s what I wanted people to take away. That’s what I took away. I wrote this book from a place at times of hopelessness, at times of being crushed by grief, but also recognizing that the worst things that I was experiencing in these past several years, 2018 to now writing the book, it wasn’t the Donald Trump re-election, but it was a murderous pandemic. It was quite a lot of injustice. They weren’t the first major injustices or the first ways in which big new institutions that rode waves of “innovation” only to oppress or to stultify had come along.

So I told the stories that made me think, okay, yes, it’s a religion, but religions can be reformed. They don’t need to be eliminated. I’m not trying to get Christianity kicked off the earth and only allowed on Mars or whatever, or Hinduism or Confucianism or Islam for that matter. I think that there are millions, if not billions of great people from those traditions, because they’re the people who have a reformed perspective, a non-fundamentalist perspective on their religions.

And what we need are technological people who recognize that these technologies can be used for medicinal purposes to allow us better access to life through transportation and housing, and a lot of really wonderful ways in which this stuff can be used. But who are going to be self-critical, non-fundamentalist, non-dogmatic, recognizing that technology can and will be abused as much as it is used to heal. And therefore there need to be real guardrails in place, real regulations, real breaking up of the biggest and most overwhelming powers, and that it’s going to be a struggle to get there. But eventually, we’ve often succeeded. And thanks to many people who may be listening to me right now, I think we will again.

Justin Hendrix:

It’s a time when people are looking for new sources of inspiration, new leaders, new paths to renewal, and I think that you’ll find many leads if that is your project in Greg Epstein’s new book. Greg, thank you very much.

Greg Epstein:

Thank you, Justin. It’s really a pleasure to talk to you. It’s a culmination of a lot of time sitting and thinking about you and the work that you do, so I really appreciate it.