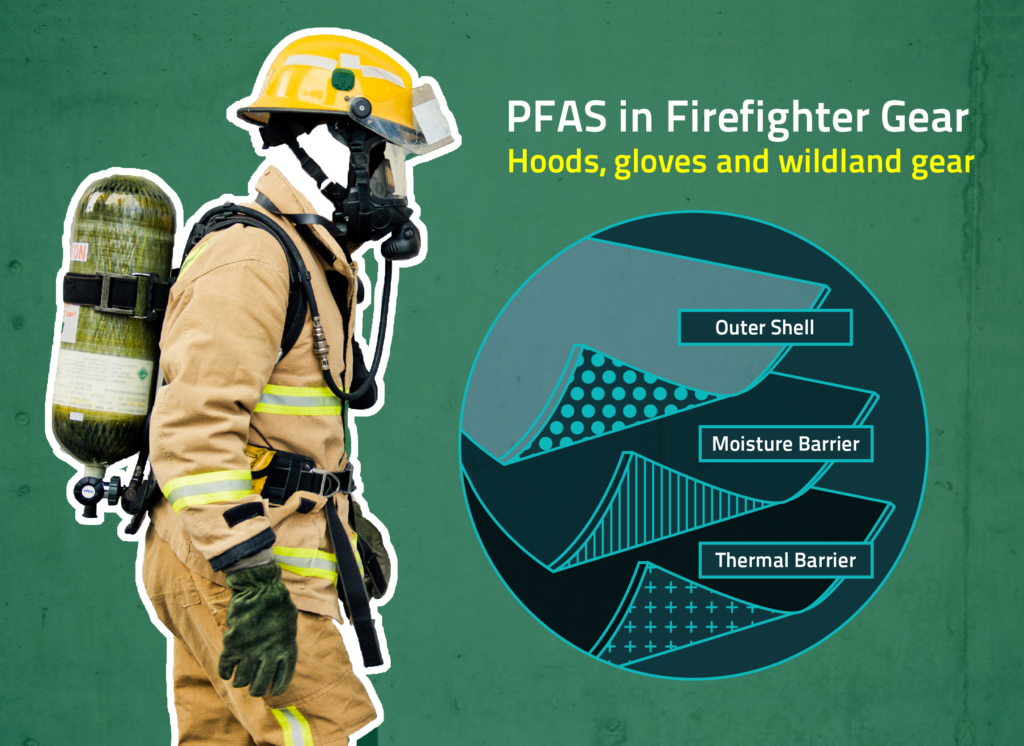

A firefighter’s protective clothing is composed of three distinct layers made of different textiles. In response to concerns about the gear possibly exposing firefighters to PFAS chemicals — several of which have been linked to cancer — NIST researchers investigated the presence of the chemicals in textiles used to make the layers. This latest study analyzed hoods and gloves worn in structural fires as well as protective clothing worn to fight wildfires.

Credit: B. Hayes/NIST

The protective clothing worn by wildland firefighters often contains PFAS, according to a new study from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The study also found PFAS in hoods and gloves worn by firefighters who respond to building fires.

PFAS — which stands for “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances” — are a category of chemicals used in a wide range of products. In high concentrations, PFAS may have harmful health effects on people.

Firefighters have more PFAS in their blood than the average person. It isn’t clear why, but one theory is that it comes from the protective equipment they wear during a fire — called turnout gear.

“Our latest study showed that PFAS are present not only in the jacket and pants worn by firefighters, but also in many of the smaller protective garments,” said NIST chemist and study co-author Rick Davis. “Measuring the presence of the chemicals is the first step in understanding their impact on firefighters.”

The NIST studies do not assess the health risks that firefighters might face due to the presence of PFAS in turnout gear. However, they provide previously unavailable data that toxicologists, epidemiologists and other health experts can use to assess those risks.

NIST conducted these studies at the behest of Congress, which called on NIST to study PFAS in firefighter gear in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act.

PFAS are everywhere. They don’t react very easily with other chemicals, so they make very effective nonstick surfaces, lubricants and food packaging. But the fact that they’re unreactive also means that they don’t break down easily. These chemicals stay in the environment for a long time, which is why they are sometimes called “forever chemicals.”

Fabrics containing PFAS are often used to make firefighting gear because these chemicals are very good at repelling water. Part of the standard for firefighter gear requires a minimum amount of water resistance to prevent steam burns and provide protection from chemicals. Water resistance also tends to make gear safer because heat can travel much more efficiently through water than through air. For example, a dry potholder will let you safely pull a hot dish out of an oven. But that same dish can give you a third-degree burn in just one second if the potholder is wet.

NIST researchers have been running a series of experiments to understand how much PFAS are in that equipment.

The two prior NIST studies looked at the level of PFAS in firefighter coats and pants and how wear and tear can increase the amount of measurable PFAS in these garments. This latest study, published on Dec. 13, analyzed gloves and hoods worn by structural firefighters (those who fight fires in buildings), as well as gear worn by wildland firefighters. The researchers were particularly interested in hoods and gloves because they come in direct contact with skin, as opposed to coats and pants that are worn over a base layer.

Wildland gear includes the protective shirt and pants worn for fighting wildfires. It’s designed for long treks over difficult terrain, so it trades off some heat protection for mobility. Unlike the thick, heavy coat and pants used to fight a structural fire, wildland gear is like something you might wear camping with extra heat protection.

The NIST team tested four types of gloves, eight types of hoods, and nine types of wildland firefighter gear from several manufacturers of firefighter gear in 2021-23. All these garments are commercially available.

The researchers pulled the garments apart into 32 textile samples and extracted PFAS from the samples into a solvent. Then they tested each solvent to see if it contained any of 55 different PFAS chemicals.

After running these tests, Davis and his team found measurable amounts of PFAS in 25 of the 32 textile samples.

Across those samples, they found 19 different types of PFAS. “There was a range in the amount of PFAS we found in each sample,” said Davis. “Most had only a little, but a few had large amounts.”

The hoods contained low PFAS levels. In almost all cases, the amount of PFAS in hood layers was too small to be measured confidently. The inside layers of the gloves had amounts of PFAS similar to those found in the inside layers of coats and pants tested in prior studies.

Wildland gear is made of only one layer. The assumption among researchers was that this layer was unlikely to contain much PFAS. In general that was true, as most of the wildland gear tested had low levels of PFAS. But there were some cases that had notably high levels. Across all the textiles tested in this study, the largest total concentration of PFAS in a single sample was about 4,240 micrograms per kilogram from a piece of wildland gear.

“We still don’t know what this means in terms of risk to a firefighter’s health,” said Davis, “but understanding where PFAS is will help us reduce potential impacts as we learn more about these chemicals.”

The researchers plan to run a follow-up study on the same samples to see how wear and tear might increase the amount of detectable PFAS in hoods, gloves and wildland firefighter gear.

Report: Andre L. Thompson et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Textiles Present in Firefighter Gloves, Hoods, and Wildland Gear. NIST Technical Note 2313. December 2024.