Over the past few years, the Lazarus group has been distributing its malicious software by exploiting fake job opportunities targeting employees in various industries, including defense, aerospace, cryptocurrency, and other global sectors. This attack campaign is called the DeathNote campaign and is also referred to as “Operation DreamJob”. We have previously published the history of this campaign.

Recently, we observed a similar attack in which the Lazarus group delivered archive files containing malicious files to at least two employees associated with the same nuclear-related organization over the course of one month. After looking into the attack, we were able to uncover a complex infection chain that included multiple types of malware, such as a downloader, loader, and backdoor, demonstrating the group’s evolved delivery and improved persistence methods.

In this blog, we provide an overview of the significant changes in their infection chain and show how they combined the use of new and old malware samples to tailor their attacks.

Never giving up on their goals

Our past research has shown that Lazarus is interested in carrying out supply chain attacks as part of the DeathNote campaign, but this is mostly limited to two methods: the first is by sending a malicious document or trojanized PDF viewer that displays the tailored job descriptions to the target. The second is by distributing trojanized remote access tools such as VNC or PuTTY to convince the targets to connect to a specific server for a skills assessment. Both approaches have been well documented by other security vendors, but the group continues to adapt its methodology each time.

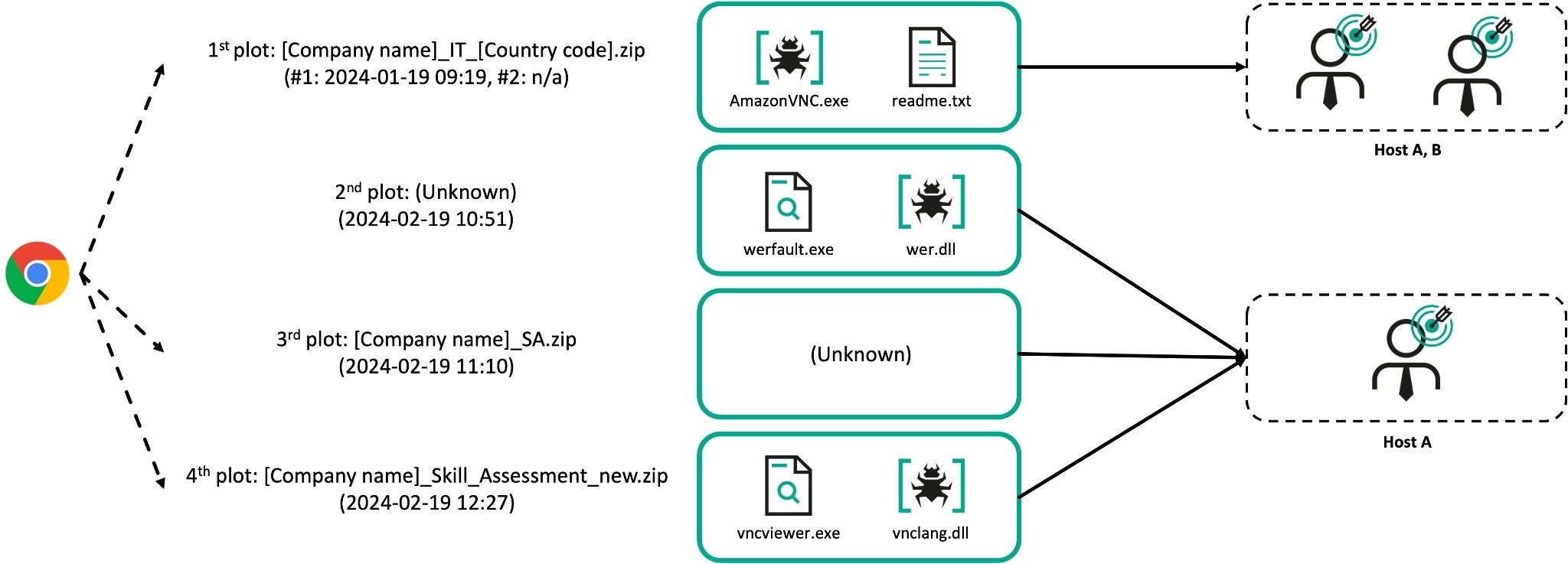

The recently discovered case falls under the latter approach. However, except for the initial vector, the infection chain has completely changed. In the case we discovered, the targets each received at least three archive files allegedly related to skills assessments for IT positions at prominent aerospace and defense companies. We were able to determine that two of the instances involved a trojanized VNC utility. Lazarus delivered the first archive file to at least two people within the same organization (we’ll call them Host A and Host B). After a month, they attempted more intensive attacks against the first target.

Appearing with state-of-the-art weapons

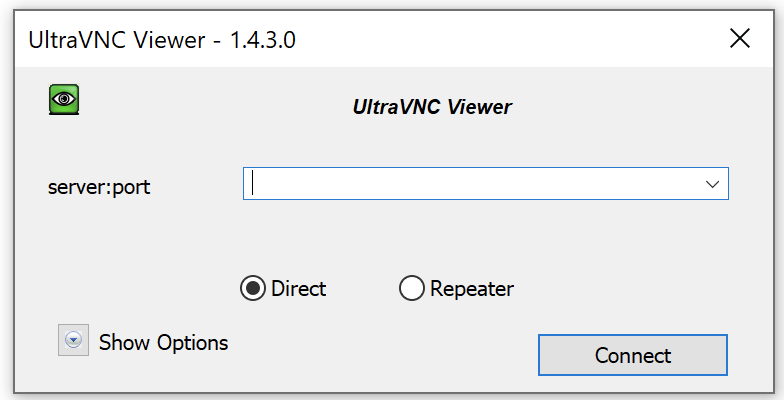

In the first case, in order to go undetected, Lazarus delivered malicious compressed ISO files to its targets, since ZIP archives are easily detected by many services. Although we only saw ZIP archives in other cases, we believe the initial file was also an ISO. It is unclear exactly how the files were downloaded by the victims. However, we can assess with medium confidence that the ISO file was downloaded using a Chromium-based browser. The first VNC-related archive contained a malicious VNC, and the second contained a legitimate UltraVNC Viewer and a malicious DLL.

|

|

Malicious AmazonVNC.exe (left) / Legitimate vncviewer.exe (right)

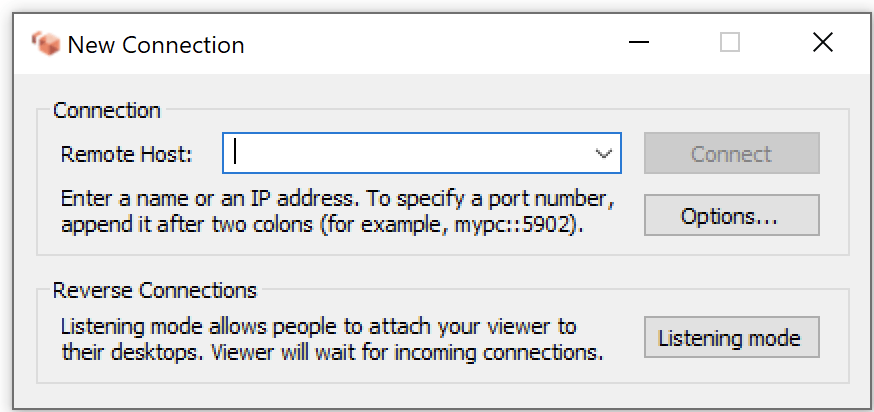

The first ISO image contains a ZIP file that contains two files: AmazonVNC.exe and readme.txt. The AmazonVNC.exe file is a trojanized version of TightVNC – a free and open source VNC software that allows anyone to edit the original source code. When the target executes AmazonVNC.exe, a window like the one in the image above pops up. The IP address to enter in the ‘Remote Host’ field is stored in the readme.txt file along with a password. It is likely that the victim was instructed to use this IP via a messenger, as Lazarus tends to pose as recruiters and contact targets on LinkedIn, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc. Once the IP is entered, an XOR key is generated based on it. This key is used to decrypt internal resources of the VNC executable and unzip the decrypted data. The unzipped data is in fact a downloader we dubbed Ranid Downloader, which is loaded into memory by AmazonVNC.exe to execute further malicious operations.

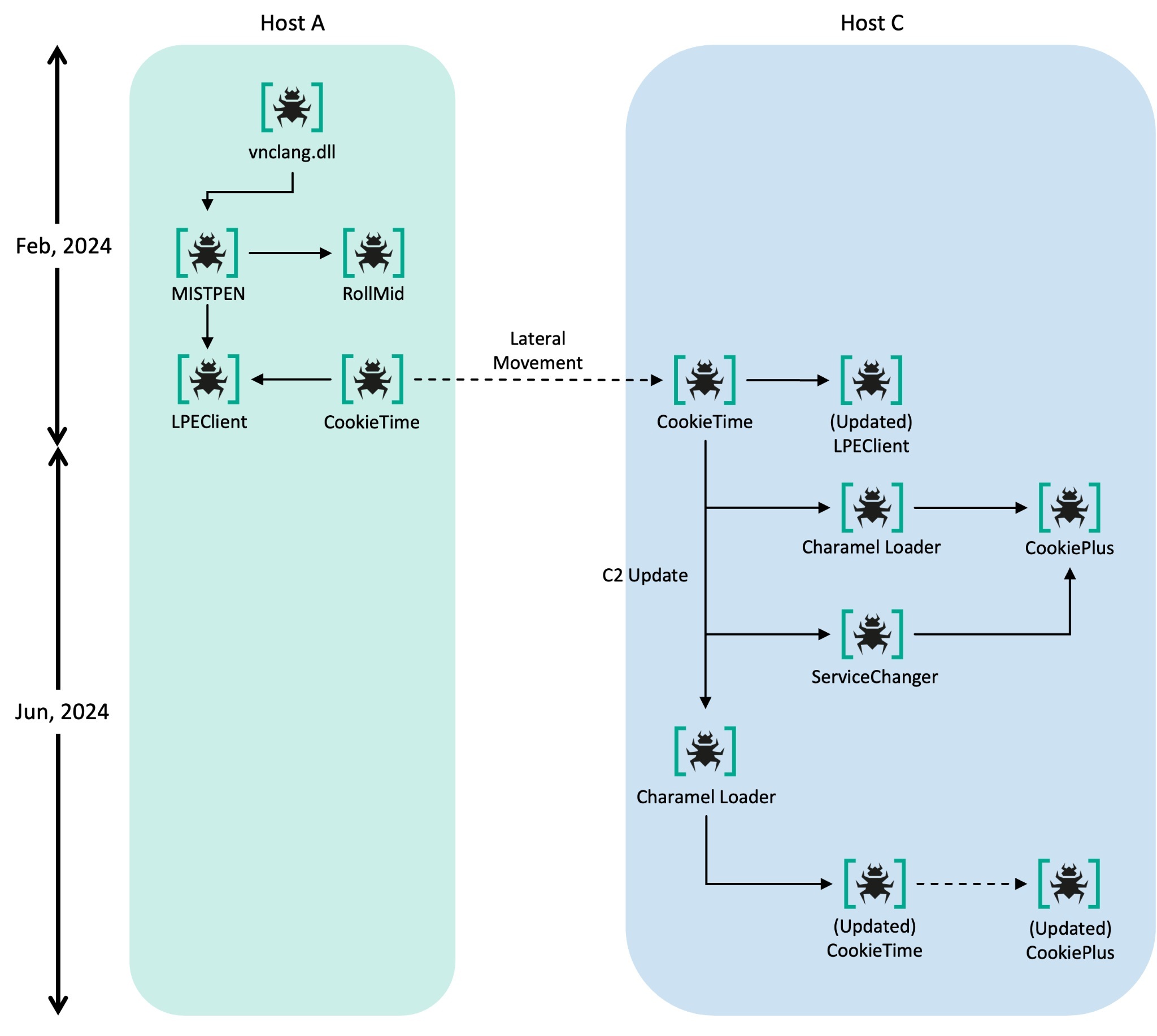

The [Company name]_Skill_Assessment_new.zip file embeds UltraVNC’s legitimate vncviewer.exe, which is open source VNC software like TightVNC. The ZIP file also contains the malicious file vnclang.dll, which is loaded using side-loading. Although we have not been able to obtain the malicious vnclang.dll, we classified it as a loader of the MISTPEN malware described by Mandiant in a recent report, based on its communication with the C2 – namely the payloads, which use the same format as payloads on the MISTPEN server we were able to obtain. According to our telemetry, in our particular case, MISTPEN ultimately fetched an additional payload under the name [Random ID]_media.dat from the C2 server twice. The first payload turned out to be RollMid, which was described in detail in an Avast report published in April 2024. The second was identified as a new LPEClient variant. MISTPEN and RollMid are both relatively new malicious programs from the Lazarus group that were unveiled this year, but were still undocumented at the time of the actual attack.

CookieTime still in use

Another piece of malware found on the infected hosts was CookieTime. We couldn’t quite figure out how the CookieTime malware was delivered to Host A, but according to our telemetry, it was executed as the

SQLExplorer service after the installation of LPEClient. In the early stages, CookieTime functioned by directly receiving and executing commands from the C2 server, but more recently it has been used to download payloads.

The actor moved laterally from Host A to Host C, where CookieTime was used to download several malware strains, including LPEClient, Charamel Loader, ServiceChanger, and an updated version of CookiePlus, which we’ll discuss later in this post. Charamel Loader is a loader that takes a key as a parameter and decrypts and loads internal resources using the ChaCha20 algorithm. To date, we have identified three malware families delivered and executed by this loader: CookieTime, CookiePlus, and ForestTiger, the latter of which was seen in an attack unrelated to those discussed in the article.

The ServiceChanger malware stops a targeted legitimate service and then stores malicious files from its resource section to disk so that when the legitimate service is restarted, it loads the created malicious DLL via DLL side-loading. In this case, the targeted service was ssh-agent and the DLL file was libcrypto.dll. Lazarus’s ServiceChanger behaves differently than the similarly named malware used by Kimsuky. While Kimsuky registers a new malicious service, Lazarus exploits an existing legitimate service for DLL side-loading.

There were several cases where CookieTime was loaded by DLL side-loading and executed as a service. Interestingly, CookieTime supports many different ways of loading, which also results in different entry points, as can be seen below:

| Path | Legitimate file | Malicious DLL | Main function | Execution type | Host installed | |

| 1 | C:\ProgramData \Adobe |

CameraSettingsUIH ost.exe |

DUI70.dll | InitThread | DLL Side- Loading |

A, C |

| 2 | C:\Windows\ System32 |

– | f_xnsqlexp. dll |

ServiceMain | As a Service | A, C |

| 3 | %startup% | CameraSettingsUIH ost.exe |

DUI70.dll | InitThread | DLL Side- Loading |

C |

| 4 | C:\ProgramData \Intel |

Dxpserver.exe | dwmapi.dll | DllMain | DLL Side- Loading |

C |

CookiePlus capable of downloading both DLL and shellcode

CookiePlus is a new plugin-based malicious program that we discovered during the investigation on Host C. It was initially loaded by both ServiceChanger and Charamel Loader. The difference between each CookiePlus loaded by Charamel Loader and by ServiceChanger is the way it is executed. The former runs as a DLL alone and includes the C2 information in its resources section, while the latter fetches what is stored in a separate external file like msado.inc, meaning that CookiePlus has the capability to get a C2 list from both an internal resource and an external file. Otherwise, the behavior is the same.

When we first discovered CookiePlus, it was disguised as ComparePlus, an open source Notepad++ plugin. Over the past few years, the group has consistently impersonated similar types of plugins. However, the most recent CookiePlus sample, discovered in an infection case unrelated to those discussed in the article, is based on another open source project, DirectX-Wrappers, which was developed for the purpose of wrapping DirectX and Direct3D DLLs. This suggests that the group has shifted its focus to other themes in order to evade defenses by masquerading as public utilities.

Because CookiePlus acts as a downloader, it has limited functionality and transmits minimal information from the infected host to the C2 server. During its initial communication with the C2, CookiePlus generates a 32-byte data array that includes an ID from its configuration file, a specific offset, and calculated step flag data (see table below). One notable aspect is the inclusion of a specific offset that points to the last four bytes of the configuration file path. While this offset appears random due to ASLR, it could potentially allow the group to determine if the offset remains fixed. This could help distinguish whether the payload is being analyzed by an analyst or security products.

| Offset | Description | Value (example) |

| 0x00~0x04 | ID from config file | 0x0D625D16 |

| 0x04~0x0C | Specific offset | 0x0000000180080100 |

| 0x0C~0x0F | Random value | (Random) |

| 0x0F~0x10 | Calculation of step flag | 0x28 (0x10 * flag(0x2) | 0x8) |

| 0x10~0x20 | Random value | (Random) |

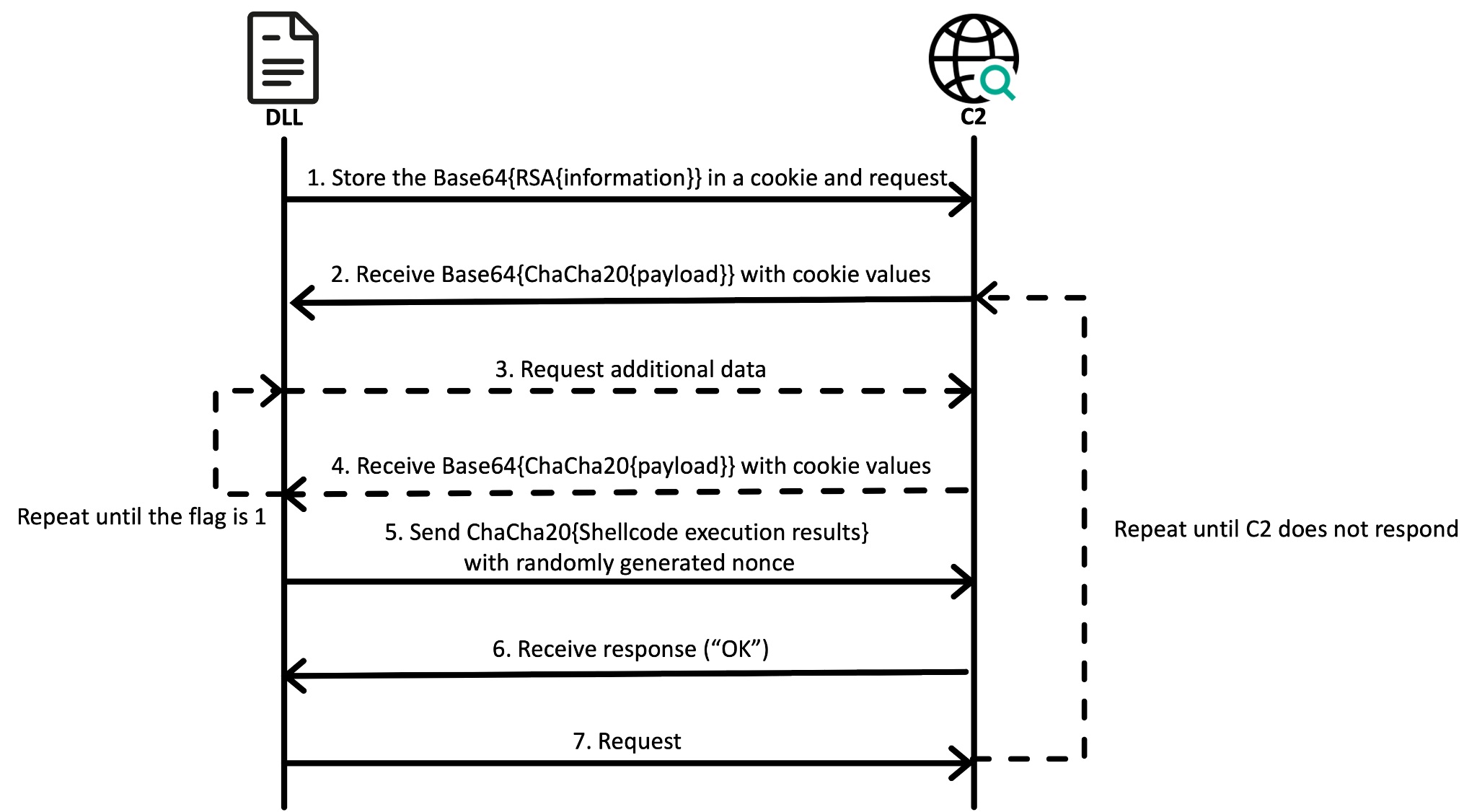

The array is then encrypted using a hardcoded RSA public key. Next, CookiePlus encodes the RSA-encrypted data using Base64. It is set as the cookie value in the HTTP header and passed to the C2. This cookie data is used in the follow up communication, possibly for authentication. CookiePlus then retrieves an additional encrypted payload received from the C2 along with cookie data. Unfortunately, during our investigating of this campaign, it was not possible to set up a connection to the C2, so the exact data returned is unknown.

CookiePlus then decodes the payload using Base64. The result is a data structure containing the ChaCha20-encrypted payload, as shown below. It is possible that the entire payload is not received at once. To know when to stop requesting more data, CookiePlus looks at the value of the offset located at 0x07 and continues to request more data until the value is set to 1.

| Offset | Description |

| 0x00~0x04 | Specific flag |

| 0x04~0x06 | Type value of the payload (PE: 0xBEF0, Shellcode: 0xBEEF) |

| 0x06~0x07 | Unknown |

| 0x07~0x08 | Flag indicating whether there is additional data to receive (0: There’s more data, 1: No more data) |

| 0x08~0x0C | Unknown |

| 0x0C~0x10 | Size of ChaCha20-encrypted payload |

| 0x10~0x1C | ChaCha20 nonce |

| 0x1C~ | ChaCha20-encrypted payload |

Next, the payload is decrypted using the previously generated 32-byte data array as a key and the delivered nonce. The type of payload is determined by the flag at offset 0x04, which can be either a DLL or shellcode.

If the value of the flag is

0xBEF0, the encrypted payload is a DLL file that is loaded into memory. The payload can also contain a parameter that is passed to the DLL when loaded.

If the value is

0xBEEF, CookiePlus checks whether the first four bytes of the payload are smaller than

0x80000000. If so, the shellcode in the payload is loaded after being granted execute permission. After the shellcode is executed, the ChaCha20-encrypted result is sent to the C2. For the encryption, the same 32-byte data array is again used as the key, and a 12-byte nonce is randomly generated. As a result, the following structure is sent to the C2.

| Offset | Description |

| 0x00~0x04 | Unknown |

| 0x04~0x06 | Unknown |

| 0x06~0x07 | Unknown |

| 0x07~0x08 | Flag indicating whether there is additional data to receive (0: There’s more data, 1: No more data) |

| 0x08~0x0C | Unknown |

| 0x0C~0x10 | Size of ChaCha20-encrypted results |

| 0x10~0x1C | ChaCha20 nonce |

| 0x1C~ | ChaCha20-encrypted results |

This process of continuously downloading additional payloads persists until the C2 stops responding.

We managed to obtain three different shellcodes loaded by CookiePlus. The shellcodes are actually DLLs that are converted to shellcode using the sRDI open source shellcode generation tool. These DLLs then act as plugins. The functionality of each of the three plugins is as follows and the execution result of the plugin is encrypted and sent to the C2.

| Description | Original filename | Parameters | |

| 1 | Collects computer name, PID, current file path, current work path | TBaseInfo.dll | None |

| 2 | Makes the main CookiePlus module sleep for the given number of minutes, but it resumes if one session state or the number of local drives changes | sleep.dll | Number |

| 3 | Writes the given number to set the execution time to the configuration file specified by the second parameter (e.g., msado.inc). The CookiePlus version with the configuration in the internal resources sleeps for the given number of minutes. | hiber.dll | Number, Config file path |

Based on all of the above, we assess with medium confidence that CookiePlus is the successor to MISTPEN. Despite there being no notable code overlap, there are several similarities. For example, both disguise themselves as Notepad++ plugins.

In addition, the CookiePlus samples were compiled and used in June 2024, while the latest MISTPEN samples we were able to find were compiled in January and February 2024, although we suspect that MISTPEN was also used in the discussed campaign. MISTPEN also used similar plugins such as

TBaseInfo.dll and

hiber.dll just like CookiePlus. The fact that CookiePlus is more complete than MISTPEN and supports more execution options also supports our claim.

Infrastructure

The Lazarus group used compromised web servers running WordPress as C2s for the majority of this campaign. Samples such as MISTPEN, LPEClient, CookiePlus and RollMid used such servers as their C2. For CookieTime, however, only one of the C2 servers we identified ran a website based on WordPress. Additionally, all the C2 servers seen in this campaign run PHP-based web services not bounded to a specific country.

Conclusion

Throughout its history, the Lazarus group has used only a small number of modular malware frameworks such as Mata and Gopuram Loader. Introducing this type of malware is an unusual strategy for them. The fact that they do introduce new modular malware, such as CookiePlus, suggests that the group is constantly working to improve their arsenal and infection chains to evade detection by security products.

The problem for defenders is that CookiePlus can behave just like a downloader. This makes it difficult to investigate whether CookiePlus downloaded just a small plugin or the next meaningful payload. From our analysis, it appears to be still under active development, meaning Lazarus may add more plugins in the future.

Indicators of compromise

Trojanized VNC utility

Ranid Downloader

CookieTime

Charamel Loader

ServiceChanger

CookiePlus Loader

CookiePlus

CookiePlus plugins

MISTPEN