La Niña conditions finally arrived last month, and for us powder hounds, that’s big news. The tropics might be thousands of miles away, but shifts in the Pacific’s sea surface temperatures can influence the jet stream, storm tracks, and ultimately how our mountain ranges stack up this winter. Let’s dig into what this La Niña means for the mid-season snow forecast.

Quick La Niña Hits

- La Niña Definition

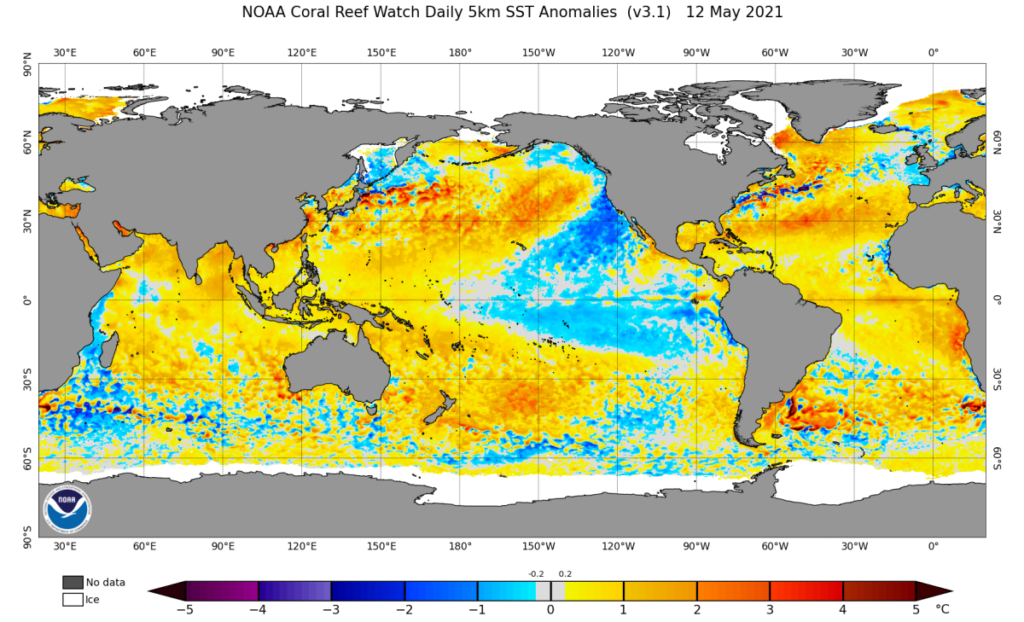

La Niña is one half of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle—when the east-central tropical Pacific turns cooler than average and the Walker circulation (the prevailing atmospheric pattern over the Pacific) strengthens. - Current Status

December data confirmed that sea surface temperatures in the Niño-3.4 region dipped to about -0.6°C below average, pushing us just over the threshold for La Niña. That’s been matched by a stronger Walker circulation (aka La Niña–like atmosphere). - Forecast Odds

There’s about a 59% chance that La Niña will hold on through February–April, then likely transitions to neutral conditions by spring (roughly 60% chance). That means this may be a shorter-lived event, although there’s still a 40% possibility that La Niña persists into March–May.

Credit: NOAA

The Ski Connection

La Niña is known for nudging the North American winter storm track in ways that can bring more cold and snow to certain regions—especially the Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies, and sometimes into the Upper Midwest. But remember, a weak La Niña doesn’t guarantee epic powder. Storm tracks vary constantly, and local weather events can buck the overall ENSO trend. Still, knowing La Niña’s influence can help us gauge which areas might see a nudge toward deeper snow totals through the second half of winter.

The Long-Awaited Arrival

We’ve been on the lookout for La Niña since last spring. She dragged her feet, but come December, all signs pointed to the big shift. Our Niño-3.4 index (which tracks tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures) finally dropped below the -0.5°C threshold, and computer models indicate it’ll stay there for the next few months. Even before the ocean cooled, atmospheric patterns—like stronger trade winds and a more active cloud/rain cluster near Indonesia—had already started looking La Niña–esque.

Why Was La Niña So Slow to Develop?

Typically, ocean cooling and atmospheric signatures develop in tandem, but this time, we saw some classic La Niña–ish atmospheric behavior well before the central tropical Pacific cooled to La Niña thresholds. One hypothesis that scientists have is that the currently record-warm global oceans might have delayed the usual feedback loop. There’s an ongoing study of a new metric, the “Relative Niño-3.4 index,” which looks at Pacific temperatures relative to the rest of the tropical oceans. By that measure, we’ve been in La Niña–like conditions for months—just not in the conventional index.

Photo: NOAA

So How Long Will This Party Last?

La Niña events can persist for several months, but nothing’s set in stone. In fact, if the three-month-average Niño-3.4 index creeps back above -0.5°C by early spring, this La Niña might not even reach the historical five-season mark typically used to classify a full-blown event. Current model guidance puts the odds at 60% that we’ll slip to neutral territory by March–May. Then again, it’s always possible La Niña hangs on longer than expected—Mother Nature loves to keep forecasters on their toes.

The most likely scenario is a weak La Niña. If the Niño-3.4 index doesn’t approach -1.0°C for a full season, we’ll be firmly in “weak La Niña” territory. Because ENSO events usually peak in winter, and because this one started later in the game, there’s limited time for it to intensify. A weak La Niña can still favor certain winter weather patterns, but its influence on large-scale temperature and precipitation anomalies may be subtle.

Already Seeing La Niña Effects?

Atmospheric changes drive ENSO’s impact on global climate, so even before sea surface temperatures officially signaled La Niña, we could’ve seen hints of it in fall weather patterns. October–December 2024 precipitation maps for the U.S. show some resemblance to what we’d expect with La Niña: a bit wetter in parts of the Pacific Northwest and drier over portions of the Southwest. Temperature-wise, the broader warming trend played a big role in the mild fall across much of the country, so pinning that solely on La Niña wouldn’t be fair.

For skiers, the takeaway is that La Niña conditions haven’t been a slam dunk for every mountain region so far, but certain areas—especially up north—are looking more promising to finish the season strong.

Bottom La Niña Line for Skiers

La Niña has arrived—finally! It’s likely to stay weak through late winter, with decent odds of phasing out by mid-spring. While weak La Niña signals typically aren’t as robust, they do tilt the odds toward cooler, wetter conditions in the northern tier of the U.S. (WA, OR, ID, MT, WY, northern UT/CO), which generally translates to better odds for scoring deep snow. But as always, local weather patterns can buck the larger trend, and we’re only halfway through the season. If you’re chasing storms, keep an eye on Powderchasers for the ever-changing details.

La Niña or not, we’re all about maximizing the best weeks of winter. Stay tuned for additional mid-season updates as the pattern evolves—and go get after that powder whenever and wherever it falls!

Related: Four to Six Feet of Snow Possible on Alaska’s Peaks—the Current State of the Snowpack

Be the first to read breaking ski news with POWDER. Subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected with the latest happenings in the world of skiing. From ski resort news to profiles of the world’s best skiers, we are committed to keeping you informed.