Cynthia interviewing a woman in Baracoa, Cuba for the symbolic meaning of her painting. Photo courtesy of Cynthia Vidaurri

We interviewed Ms. Vidaurri about her connections to the museum and its mission, her research, how she finds inspiration, and future projects. The following are her answers.

Can you share a bit about yourself and your cultural background?

My name is Cynthia Vidaurri. I was born in San Antonio, Texas and grew up in Robstown, a small community outside of Corpus Christi, Texas. This is always such a complicated question. The processes of cultural and genetic mixing in Mexico were significantly different from that of the United States. That history makes it very difficult to explain our experiences in US terms. In Mexico, approximately 60-90 percent of the population identifies as mestizo—part Indigenous and part European. I identify as Indigenous mestiza. With the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 70s, many Mexican Americans that had been detribalized over generations, were emboldened to publicly recognize their Indigenous roots, and recovered many cultural practices we see in the US today. Currently there are many debates on what it means to be Indigenous in Mexico. The complexity of this topic really merits a longer conversation.

How did you initially become involved with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI)?

I was asked to serve as curatorial advisor to the team that was curating the opening celebration of the museum in Washington, DC, which opened in September 2004. I worked with NMAI staff in the planning of the event content. The event was kicked off with a procession of Native peoples from the hemisphere followed by several days of music and dance presentations.

Why is it important for the NMAI to tell the stories of the American Southwest and Mexico?

It is important for the NMAI to tell stories of the American Southwest and Mexico as well as the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean for several reasons. Our collection holds objects from throughout Latin America and our museum has a hemispheric mandate. In the case of Mexico, it is important to remember that before we had our current political national boundaries, people moved with great ease. There is evidence of early trade and movement of people throughout Mexico and the US Southwest and even beyond that region. In more contemporary times, Indigenous Mexicans came to the United States during the Bracero Program from 1942 to 1964. Currently, there is a considerable amount of Indigenous Mexican migration to the United States. It is interesting to observe how this migration impacts ideas of indigeneity and how exchanges with US Indigenous communities impact home countries.

Where have you done research with Indigenous communities?

The bulk of my work has been in Mexico and Cuba. I have also been fortunate to work with Indigenous communities from Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Panama, Columbia, and Chile.

An Arhuaco leader from Colombia putting a woven bracelet on Cynthia. The bracelet signified a commitment to the work that the museum was doing on representing the Arhuaco culture in an exhibition. Photo courtesy of Cynthia Vidaurri

What is your area of cultural specialty?

As a folklorist my work is focused on traditional culture. This doesn’t mean that it is “old-time” cultural. It is more accurate to say that we work in the field of home and community culture. However, there are younger folklorists who are conducting research in the digital sphere. I am particularly interested in traditional medicine and belief systems, the intersection of tourism and Indigenous craft production, and how traditional culture is used to maintain and defend cultural sovereignty.

Can you give our reading audience a short definition of the Day of the Dead?

Day of the Dead is an act of remembrance to commemorate our departed loved ones. In the most traditional sense, it is a time when the departed return to us and we welcome them with their favorite foods, beverages, and other items they enjoyed when they were alive. We create ofrendas (altars) where these items are placed. Other objects on the ofrendas are there to facilitate their return to this earthly existence. This cultural expression exists in several Latin American countries, but the tradition most known in the United States stems from Mexico. Mexico’s Day of the Dead, as practiced by Indigenous communities, has been inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

How long have you been participating in and documenting the practices associated with the Day of the Dead?

I’ve been documenting Day of the Dead practices for some thirty years. My personal commemoration started after my father passed away. Over the years, friends and other family members have added photos of their loved ones to the ofrenda. This year, we are hosting a community ofrenda where our neighbors can also participate.

How has the Day of the Dead changed in your lifetime?

There have been some dramatic changes in Day of the Dead practices. Over the years new elements have been introduced to the ofrendas. Perhaps most interesting is that non-Mexican and non-Indigenous peoples have begun the practice. It is concerning that Day of the Dead has been reduced to a costume by some non-community members and the event has been commercialized by business entities. There is no end to the variety of Day of the Dead products that can be purchased on the internet. Also, through mass media and tourism, Day of the Dead is now known in Europe and Asia.

What inspired you to write about the background of the Indigenous dog breed associated with the Day of the Dead?

I’ve had a personal interest in the xoloitzcuintli breed for some time, but until recently, it was difficult to find a breeder. About a year and a half ago, I finally acquired a puppy, and my life hasn’t been the same since.

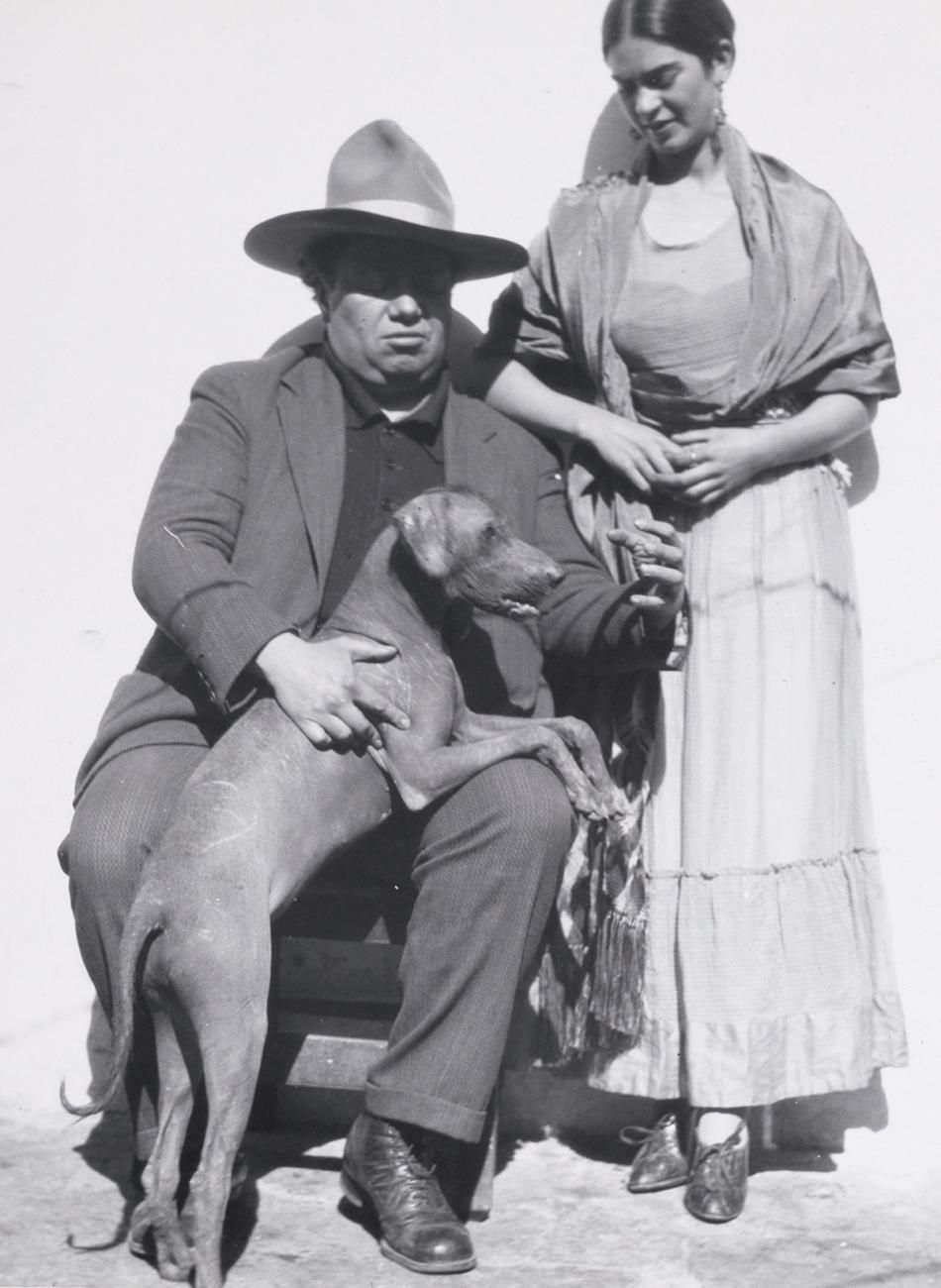

Mexican artists Diego Rivera (left, with dog) and Frida Kahlo helped revive the xoloitzcuintli breed. Although the dogs are typically seen with upright ears, large xolos sometimes have floppy ones, so this may be one of the couples’ many xolos. Florence Arquin Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. 19798

Can you share a preview quote from your recent article “Mexico’s Legendary Xoloitzcuintli, the Hairless Dog” featured in the Fall 2022 issue of American Indian Magazine?

“Humans have an undeniable bond with their dogs. This has been evident in Mesoamerica since before Spanish colonial contact in the early 1500s—particularly with the “xoloitzcuintli” (pronounced show-low-eats-queen-tlee). The name of this breed is certainly a mouthful, and given this and that many of these dogs are mostly without fur, it is no wonder that many English speakers simply call this breed the “Mexican hairless.” That name, however, does not reflect its significance in Mesoamerican history and culture. (Xoloitzcuintli is sometimes shortened to xolo.)

What are some examples of how the Mexican Indigenous dog breed is used in popular culture?

The breed has become more popular since the release of the film Coco that features a xoloitzcuintli named Dante. Xoloitzcuintli imagery can be found everywhere these days. These dogs can be found on anything from coffee mugs, to piñatas, t-shirts, and tattoos.

How do you choose topics to write about?

There is so much work to be done in the field of traditional Indigenous culture that there is never a shortage of topics to research and write about. I tend to write about topics of interest to the communities with whom I’ve worked.

Cynthia in a group photo with field research workshop participants in Cambodia. Courtesy of Cynthia Vidaurri

What are some of your future projects or goals?

In the future, I would like to develop a digital exhibition on Mexican huipiles, a traditional blouse used by Indigenous women since before Contact. These garments are an important reflection of community identity that is replicated in the weaving and embroidery designs. This garment has become a popular tourist craft which has important impacts to the production of huipiles.

What message would you like to share with the youth of the Latino community?

I would like to encourage young Latinos to learn about the Indigenous peoples of their home country and explore their own Indigenous roots. Sadly, in many Latin American countries, to be Indigenous was something to be embarrassed about. Through the years, many have lost those cultural connections.