On a cold, rainy day in December 2016, teacher and activist Abdulkafi Alhamd collapsed on the balcony of his Aleppo apartment building, across from a pile of rubble. Pro-government forces, supported by Russian forces, have advanced into the last rebel-held areas of the Syrian city. He spent months documenting the death and destruction around him in hopes that other countries would end the violence. Alhamd made his final deployment from Aleppo before evacuating with his wife and 10-month-old daughter.

Staring into a cellphone camera, he spoke of losing faith in the international community, expressed concern for his family and lamented the sight of pro-government soldiers mourning the corpses of rebel fighters. A gunshot rang out behind me. “At least we know we were a free people,” he said before concluding.

For the past eight years, Alhamd has lived in the town of Darat Izzah, located in rebel-held countryside about 32 miles outside Aleppo. He teaches English literature at the Free University of Aleppo while raising three young children, ages 8, 6, and 19 months. He often spoke to his children and students about his home in Aleppo and his desire for freedom from President Bashar al-Assad’s government. And he swore to himself that if the city was liberated, he would be the first to return.

Last Friday, as rebel forces advanced on Aleppo, the country’s second-largest city, in a surprise attack, Alhamd jumped into a car and drove toward the city with a friend. Although rebel fighters warned him that fighting was still going on, he insisted and passed through the checkpoint. His first stop was an old apartment. So he shot a new video showing the exact spot he sat in 2016, this time to celebrate his return.

“You can’t imagine what I was feeling,” Alhamd told The Intercept. “I was running like a child. I was crying and crying.”

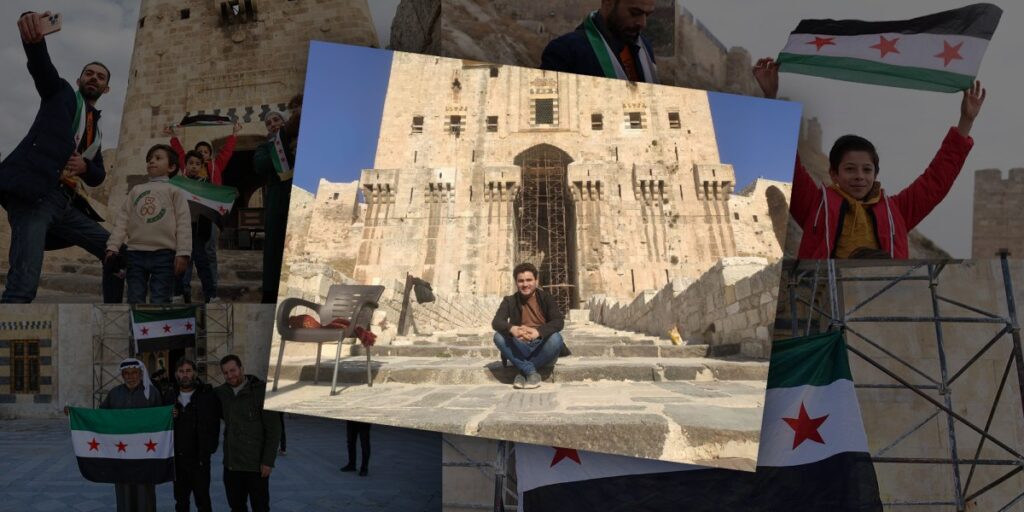

Anti-government fighters celebrate on the streets of Aleppo, Syria, December 3, 2024. Photo: Ugur Yildirim/DIA Images/Abaca/Sipa USA via AP

Alhamd is one of many Syrians who returned to Aleppo for the first time in nearly a decade, celebrating the opportunity to return to their homes and reunite with relatives and friends. There has been a lull in the civil war since 2020, after the Syrian government, working with Russian forces and Hezbollah fighters, defeated rebels and regained much of the country.

But the rebels have been on the offensive in the past week, with Russia’s attention focused on the war in Ukraine and Hezbollah weakened by its conflict with Israel. The rebels, led by the most important faction, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), are moving south toward the capital, Damascus, and claim another major city, Hama. On Friday, they threatened to retake the city of Homs, a Russian naval base and Damascus, a key link between Syria and Lebanon.

The United Nations later called for a ceasefire, citing growing humanitarian concerns. The recent Syrian civil war has left more than 280,000 Syrians internally displaced, according to the United Nations’ World Food Programme. Another 500,000 Syrian refugees recently returned from Lebanon, fleeing an Israeli bombing campaign. The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights also said at least 98 civilians have been killed in the first week since fighting resumed in northwest Syria, including in rebel-held Idlib. and 85 civilians from Russian airstrikes on rural Aleppo. (Russian and Syrian attacks on Idlib and other areas of northwestern Syria intensified ahead of the ongoing rebel offensive.)

Assad’s regime is responsible for war crimes and repressive tactics such as the torture and mass incarceration of civilians who go missing in the country’s prisons. HTS leadership previously had ties to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, but its leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani said his group has since severed those ties, evolved from its jihadist roots and , said that they accept ethnic ideology. minority group.

Alhamud said he has been vocal about some of HTS’s past actions, but welcomes its evolution. As he walked through Aleppo this week, he said he was not affiliated with any particular rebel group and was only interested in fighting “oppression in whatever form it takes.”

Mai Elsadani, executive director of the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, said it was a balancing act for Syrians such as Alhamd. “It may be true that you are a staunch opponent of the Assad regime, which has committed war crimes of a horrific nature, and that this is a serious threat to the brutal regime that has silenced so many and displaced so many. We can also celebrate the fact that it is a challenge that has separated many people’s families and turned what started as a peaceful uprising into a proxy war,” El-Sadani said. “We can recognize all of this while taking a wait-and-see approach, or organizing and saying that people cannot accept a society in which all citizens are not equal.”

Syrians walk through Saadara al-Jabiri Square in Aleppo on December 5, 2024. Photo: Omar Haj Kadou/AFP via Getty Images

In 2011, during the Arab Spring, when many Arab countries rose against their governments, Syrians began protesting against the Assad family’s Baathist dictatorship, which had ruled the country for more than 50 years.

Alhamd had participated in pro-democracy demonstrations in Aleppo in 2011, hoping for a peaceful end to Assad’s regime. “My life started with a revolution,” he said, and the protests infused him and his friends with meaning and hope. “Before that, I don’t think I’m alive.”

The crackdown on protesters was severe, with government soldiers firing into crowds and shelling the streets with tanks and heavy weapons. The revolution eventually evolved into the ongoing civil war, which over the past decade has become a proxy war between various countries with imperialist ambitions and interests in the region, including Russia, Iran, Turkey, and to some extent the United States. Ta. The civilian death toll exceeds 300,000, the majority killed by the Syrian government and its allies in a punitive bombing campaign that destroyed large parts of many cities, including Aleppo.

When Alhamd returned to Aleppo last week, he visited the graves of friends killed in the war. While there, he cried, prayed and asked for forgiveness for leaving them behind when he was evicted in 2016. He then visited the Quake, an ancient waterway that runs through the city. At least 230 bodies were washed there in 2013. Many of those pulled from government-controlled areas had gunshot wounds to the head, their hands tied behind their backs and their mouths taped shut. Human rights groups blame the Assad regime for their deaths.

“We found dozens of bodies, dozens of souls in our region that are crying out for justice. That’s why we’re here to get some justice for those who didn’t have it. , we are back in Aleppo,” Alhamd said in a statement. A video of him standing in front of the river. “World, you also have a responsibility to hold accountable those who commit these crimes.”

Once the rebels entered Aleppo, they took control of the prison and freed the imprisoned population. Many said they had been unfairly imprisoned by the Assad regime and falsely accused of being members of the rebel group. A man interviewed by a Syrian journalist said he was released this week after being imprisoned for eight years. He reported being tortured after being accused of being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. During interrogation, the man broke down in tears, crying out, “Fuck you, al-Assad,” before saying he planned to return to his wife and two children, whom he had not spoken to since his arrest.

Similar scenes occurred in Hama, where rebels released dozens of other political prisoners. The city’s occupation also had a significant impact on the population, which is still healing from the 1982 massacre in which Assad’s father, Hafez, oversaw the killing and disappearance of at least 10,000 people. Earlier this year, Switzerland issued an arrest warrant for war crimes charges against Hafez’s brother Rifaat al-Assad, who still lives in Syria, for his involvement in the genocide. Videos posted on social media showed people in Hama cheering as a large statue of former President Hafez al-Assad was toppled with a crane.

A billboard with a photo of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the national flag is torn down by rebel fighters in the northern city of Aleppo on November 30, 2024. Photo: Omar Haj Kadour/AFP via Getty Images

By returning to Aleppo, Alhamd was able to reunite with his sister, aunt, uncle and father, whom he hadn’t seen in 20 years. Her father immigrated to Saudi Arabia in 2004 and returned 10 years later, but while he lived in a regime-controlled part of the city, Alhamd lived in a rebel-held part of the city. When they met again, his father (85 years old) hugged him tightly, kissed him many times, and said he never thought he would live to see him again.

This return also meant that Alhamd was able to show his children where his family came from. They met their grandfather for the first time. He also took them to major landmarks such as the ancient Aleppo Citadel. For the past eight years, he has been showing them photos of the city, sharing memories and telling them that even if he can’t make it in his lifetime, he will visit someday.

“After liberating Aleppo, they realized that they did have roots,” Alhamd said. “They have a history and they have relatives.”

Despite their newfound freedom, many in his family still fear Assad’s regime. Before the latest attack, government agents had visited Alhamd’s father’s home to inquire about his son’s whereabouts. Alhamd suspected they labeled him an enemy because of his outspokenness against the Assad regime online and in Western media. He said his father had to bribe a police officer to leave him alone.

After returning home, when he tried to visit his relatives, his uncle refused to open the door. Several friends also sent text messages to Alhamd, telling her not to greet him if they met in public. Alhamd said her family and friends fear they will be punished for associating with them if the Assad regime retakes Aleppo.

Alhamd, who teaches an English literature class at the Free University of Aleppo, likens the Assad regime’s influence to Big Brother in George Orwell’s novel “1984.” Like Big Brother, the leader of a totalitarian state in a dystopian novel, pictures of Assad are all over the city. “And people are always afraid of him, even if he’s not there,” he said.

In class, Alhamd uses the book to teach students why Syrians rose up against the government, many of them too young to remember the early days of the revolution and civil war. Big Brother is created by our silence, he tells them.

Before returning to Aleppo, Alhamd said he had recurring nightmares, which he said are shared by many Syrian refugees. In his nightmare, he was trapped in Aleppo or another government-controlled city with no way out. He recalled the nightmare when he returned to the city last week and passed buildings with pro-government slogans on the walls along with pictures of President Assad. And he had to remind himself that he was awake.

“When I first went there, I always prayed to God, ‘Please tell me this is not a dream,'” he said.