Fear is normally the root of tragedy.

On December 29, 1890, that was the case: The Wounded Knee Massacre. This event was precipitated by the United States government’s fear of an uprising due to the practice of the Ghost Dance, a new spiritual practice introduced to the Native Americans by a Paiute shaman called Wovoka. The foundation of the practice was based on a vision that if the Ghost Dance was performed ardently across Indian Country, the white settlers would be buried by a tidal wave of earth and Native ancestors would rise, returning the land to its pre-colonized state.

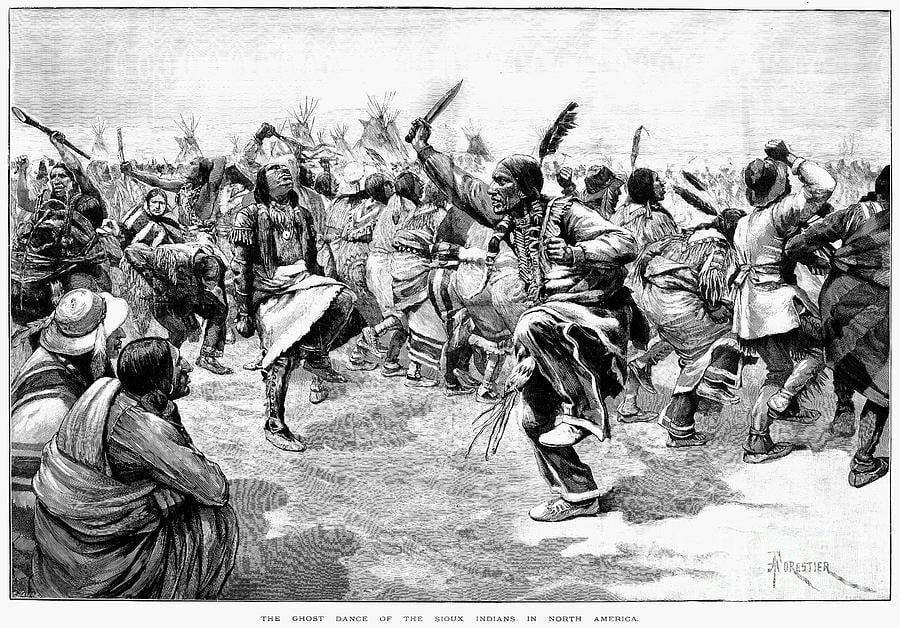

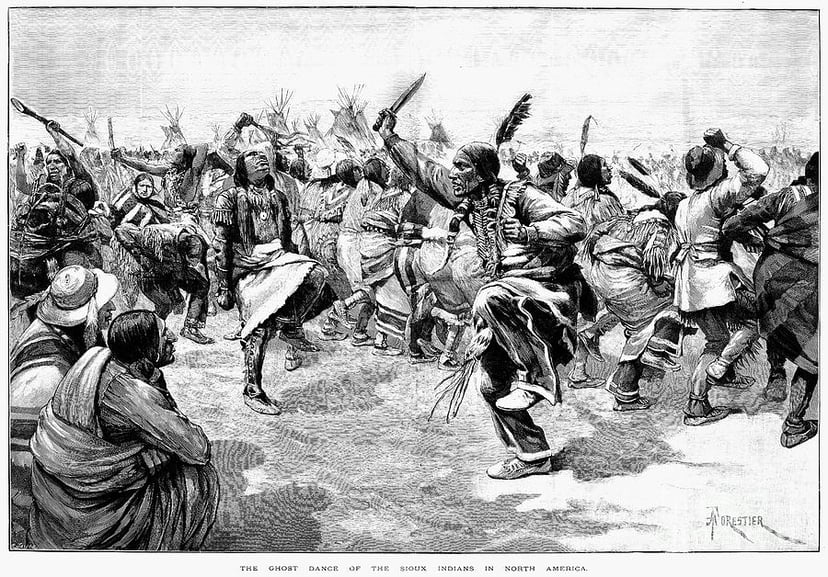

The Dance that Inspired Hope and Fear

Men who danced the Ghost Dance wore white shirts bearing brightly colored eagles, buffalo, and other significant symbols—these shirts were “armor” against bullets. Followers of the Ghost Dance believed the shirts could not be penetrated by bullets. The dance, performed in a circle to drums and singing, was intense, but peaceful. However, to the U.S. troops living amongst these “troublemakers,” the dance was intimidating and was spreading across the Plains like wildfire in Lakota’s attempt to restore life as they once knew.

“A desperate Indian Agent at Pine Ridge wired his superiors in Washington, ‘Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy….We need protection and we need it now. The leaders should be arrested and confined at some military post until the matter is quieted, and this should be done now.’” Fear at its best.

“A desperate Indian Agent at Pine Ridge wired his superiors in Washington, ‘Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy….We need protection and we need it now. The leaders should be arrested and confined at some military post until the matter is quieted, and this should be done now.’” Fear at its best.

Result of the Fear from the Ghost Dance

.jpg?width=204&name=Sitting%20Bull%20(Case%20Conflict).jpg) Prior to the Wounded Knee Massacre, December 15, 1890, Chief Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa leader who led the victory over the U.S. Calvary at Little Big Horn [Greasy Grass] along with approximately 9 followers, died from a gunshot wound when nearly 43 tribal policemen attempted to arrest him for his role in allowing the Ghost Dance religion to spread among his people.

Prior to the Wounded Knee Massacre, December 15, 1890, Chief Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa leader who led the victory over the U.S. Calvary at Little Big Horn [Greasy Grass] along with approximately 9 followers, died from a gunshot wound when nearly 43 tribal policemen attempted to arrest him for his role in allowing the Ghost Dance religion to spread among his people.

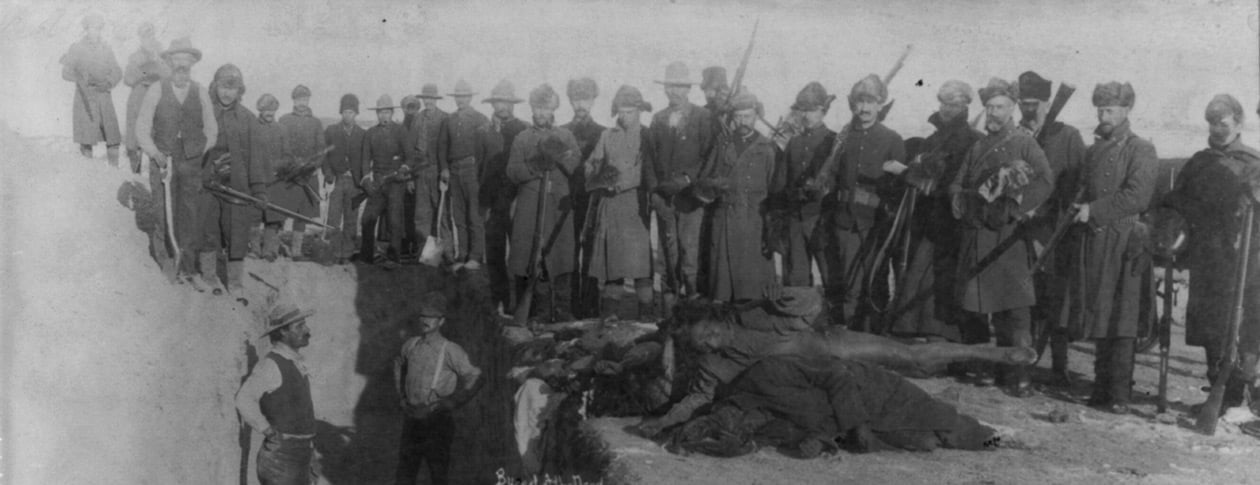

Miniconjou Lakota Chief Sitanka, known as Big Foot, led 350 Miniconjou followers to Pine Ridge to meet with the Oglala Chief Red Cloud in hopes of finding a peaceful resolution. U.S. military intercepted the group at Wounded Knee Creek, 20 miles from Pine Ridge Agency, and forced them to make camp.

The 7th Calvary of the United States, led by General Forsythe, positioned four Hotchkiss guns on a hilltop, rounded up Miniconjou, and demanded the surrender of the encampment’s weapons. Big Foot relinquished some but not all weapons. During the process of gathering weapons, one Lakota man’s weapon fired, setting off all-out gunfire and sending women and children running toward the creek for shelter. The military unloaded fire from the Hotchkiss guns relentlessly killing most in camp—only around 50 survived the event.

Photo: The Library of Congress

Ultimately, this fear of the Plains Indians and their attempts to survive the forced assimilation to reservation life resulted in the massacre of nearly 300 Lakota—mostly women and children.

Seeking the Truth about the wounded knee massacre

This retelling of the complicated, capstone incident, one that would end the Ghost Dance movement, is not meant to oversimplify the massacre nor the events surrounding it. Wounded Knee remains one of the largest mass killing by the U.S. military on American soil, but it will NOT be listed as such. Originally, the U.S. government called it a battle, but after investigation and eye-witness accounts, it was indeed ruled a massacre. Most of the victims were unarmed. It was a tragedy—one based on fear.

In order to view this in proper perspective, we need to re-evaluate historical accounts and the role colonization played in the current issues facing Native Americans. Wounded Knee must remain at the forefront as a reminder that in order to combat fear along with its outcomes, we must understand the truth and find ways to solve the historical trauma created in the wake of tragedy.

Please help us raise awareness by sharing this story and the story of Native Hope with your friends and family! When you support Native Hope, you are investing in giving HOPE to the voices unheard.