Residents were already on edge as more fires erupted across the Los Angeles region, traumatising millions of people who feel that after four days there’s no end in sight.

Then on Thursday afternoon came another jolt in the form of a text alert.

This one was mistakenly sent to every cell phone in the county – home to about 10 million people – warning them the blaze was close and they should prepare to evacuate.

Rebecca Alvarez-Petit was on a video work call when her phone started blaring.

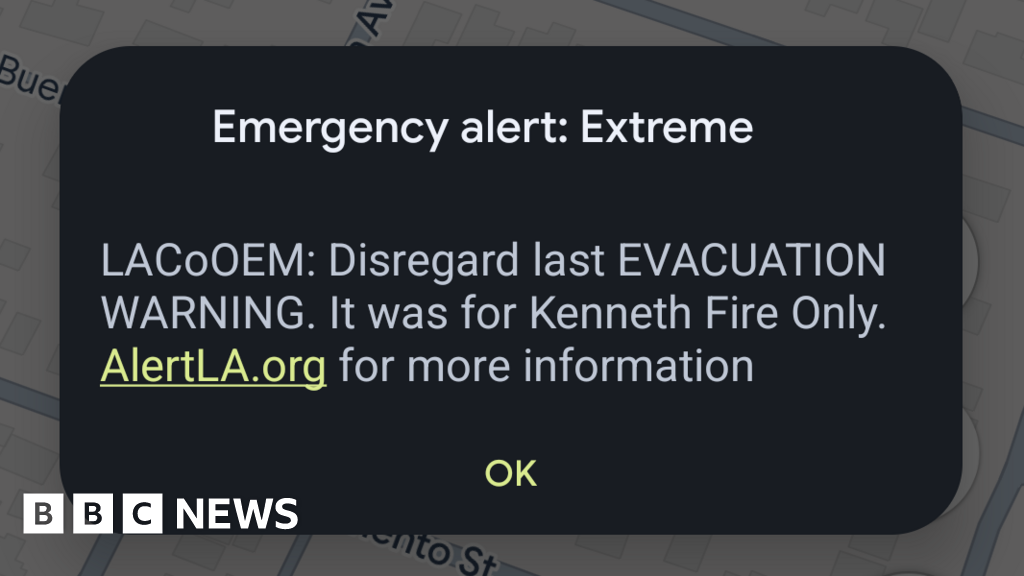

“An EVACUATION WARNING has been issued in your area,” the text message said.

The sound echoed around her as each of her colleagues received the same startling message.

“It was like a massive panic that I was watching in real-time,” she said.

She and colleagues started researching and trying to see whether they were in imminent danger.

Instant relief came in the form of a corrected alert telling them to disregard the warning but this soon gave way to newfound anger, she said.

“We’re all on pins and needles and have been anxiously sitting by our phones, staring at the TV, having the radio going – trying to stay as informed as possible because there wasn’t a good system in place,” said Ms Alvarez-Petit, who lives in West Los Angeles.

“And then this. It’s like – you have got to be kidding me.”

The death toll from the wildfires has continued to climb with at least 10 people known to have died and that toll may grow.

For many, the anxiety about saving lives and property has turned into a sense of frustration over the handling of the fires.

A mayor’s frustration

Officials have acknowledged some of the complaints, from hydrants running dry that hindered firefighting efforts to questions about preparedness and fire mitigation investment.

But asked about the alert message mistake, Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass mostly deflected, saying she planned to visit as many affected areas as possible and speak to residents in an effort to rebuild trust.

“We’re doing everything we can, and success is being reported,” she said, urging LA residents to have faith in their officials.

Other officials at the same news conference, including those who manage emergency alerts such as the one sent, apologised for the mishap, expressed frustrations over the error and promised to examine how it occurred.

The mayor went on the defence again when pressed on the city’s response more broadly.

“We’re not going to allow politics to interfere, and we’re not going to allow politics to divide us,” she said.

Bass had returned to the city from a pre-planned trip to Ghana to find it on fire. She faced intense questions on Thursday about the region’s preparedness, her leadership in this crisis and the water issues that failed firefighters.

“Was I frustrated by this? Of course,” Mayor Bass said on Thursday, answering a question about water issues and whether the area was prepared enough. She noted that is an “unprecedented event”.

Like other officials, she stressed the fires were able to spread on Tuesday because of strong winds – the same winds that prevented aircraft from dropping water or fire retardant on the blazes. She said urban water systems and neighbourhood fire hydrants are not built to handle dousing thousands of acres of fire.

She noted there will be reviews of how the incident unfolded that will examine how officials and agencies handled it.

“When lives have been saved and homes have been saved, we will absolutely do an evaluation to look at what worked, what didn’t work, and to correct or to hold accountable any body, department, individual,” she said.

“My focus right now is on the lives and on the homes.”

Water shortage questions

The evolving disaster has turned into a need to understand why this happened and how it escalated into the most destructive fire in the history of Los Angeles.

As one of the now five fires burning in Los Angeles County approached Larry Villescas’ home on Tuesday, he grabbed the only tool he could – a garden hose.

He and his neighbour made quick work of the embers falling on their homes from the Eaton Fire and igniting grass.

Then the hose ran dry.

He watched his neighbours’ home in Altadena ignite. Then there was a boom – a nearby home was ablaze and sounded as though it exploded. He had to leave.

As he drove away, he watched the fire take hold of his garage.

“If we had water pressure, we would have been able to fight it,” Mr Villescas said, standing in front of the charred remains of his home.

He remembered seeing firefighters that night – as the community burned – sitting in their trucks, unable to help.

“I remember my rage. It was like ‘do something,’ but they can’t – there’s no water pressure,” he said. “It’s just infuriating. How could this happen?”

Some experts have said the water shortage is due to unprecedented demand not mismanagement.

“The problem is that the scope of the disaster is so vast that there are thousands of firefighters and hundred of fire engines drawing upon water,” Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the California Institute for Water Resources, told the BBC.

“Ultimately only so much water can flow through pipes at a time.”

Other neighbours shared their sense the state was not prepared despite routinely seeing destructive fires.

Hipolito Cisneros, who was surveying the remains of his now-destroyed home, said the public utilities in the area have needed upgrades for years.

“We’ve lived here for 26 years and we’ve never seen it tested,” he says about the fire hydrant at the end of his block that failed to draw water when it was needed most.

Down the street, Fernando Gonzalez helped his brother sift through the rubble of his home of 15 years.

He noted that his own home in Santa Clarita – about 45 minutes away in Los Angeles County – was also being threatened by a different set of wildfires.

“We’ve just been on high alert,” he said. “It’s all around us, you know.”