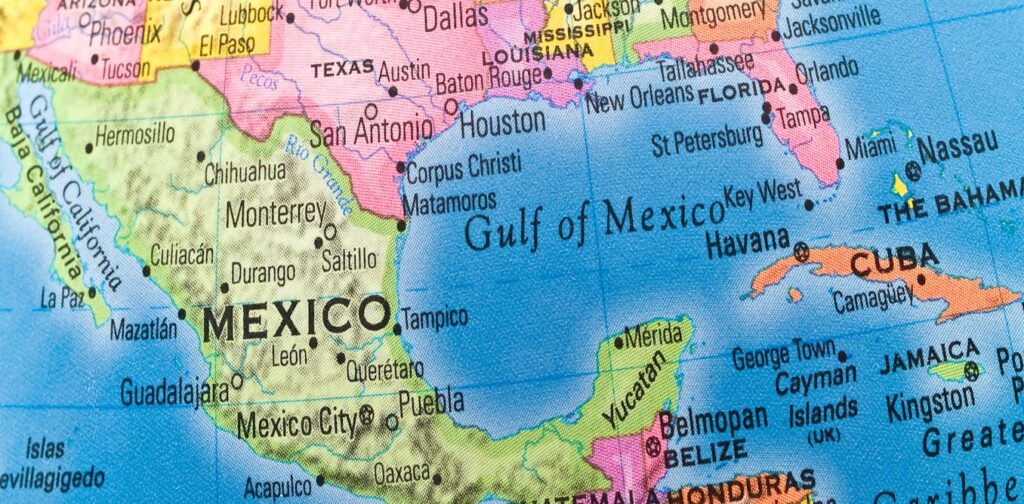

Among the flurry of executive orders issued by Donald Trump on his first day back in the Oval Office was one titled “Restoring a Name that Celebrates America’s Greatness.” The “area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico” was unilaterally renamed the “Gulf of America.”

The order notes that this maritime space has long been a “vital asset” to the United States, with its “rich geology” producing about 14 percent of U.S. crude oil production, “vibrant U.S. fisheries,” and justified by being a “favorite destination”. American Tourism”.

The Gulf was also characterized as an “indelible part of America” that will continue to play “a vital role in shaping America’s future and the global economy.”

But while this part of the Atlantic is undoubtedly important to the United States, it also has implications for other countries. So can a president really change his name? of course! At least as far as the US is concerned, anyway.

naming rights

The relevant federal agency is the Board of Geographical Names (BGN). This committee was established in 1890 to standardize the use of geographic names.

Specifically, President Trump’s executive order directs the Secretary of the Interior to change the name to Gulf of America, ensure all federal references reflect the name change, and update the Geographic Name Information System. It instructs them to take “all appropriate actions” to renew it.

BGN has generally been reluctant to change commonly accepted geographical names. However, the executive order makes clear that the composition of the board may change to ensure the proposed name change is implemented.

But whatever the United States chooses to call the Gulf, that doesn’t mean other countries will pay attention. Indeed, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo immediately hinted at the possibility of renaming the United States itself Mexican America.

She argued that Mexico and the rest of the world will continue to use the name Gulf of Mexico, citing a 17th-century map that shows that name for much of the area that now makes up the United States.

Donald Trump signs an executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico in the Oval Office on January 20. AAP

controversial history

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) publishes a booklet called “The Limits of Oceans and Seas,” which lists the names of seas and oceans around the world, including the “Gulf of Mexico.”

However, the study makes clear that these restrictions have “no political meaning whatsoever” and are “solely for the convenience” of the Hydrographic Office in preparing information for seafarers.

This book has not been published since 1953. To be precise, this was because there was a dispute between Japan and South Korea over the place names of their bodies of water. Japan prefers to call it the Sea of Japan (as many know it), but South Korea has long campaigned for it to be named the East Sea or East Sea/Sea of Japan.

A revised version of the IHO, submitted to member states in 2002, addressed this issue by omitting coverage of the East Sea/Sea of Japan. It remains as a working document only.

South Korea takes this issue so seriously that an ambassador-level position was created and the Tokai Association was established 30 years ago to address the issue.

That this impasse has prevented new editions of IHO publications for more than 70 years reflects not only the difficulty of changing commonly known geographic names, but also the importance countries place on these issues. It shows what you are doing.

dangerous ground

Place names, known as toponyms, are sensitive because they indicate that any country has the right to change their name, implying sovereignty and ownership. Names therefore have historical and emotional significance and are quickly politicized.

This is especially true where past conflicts with unresolved legacies or current geopolitical conflicts are at play. For example, the Sea of Japan/East Sea dispute dates back to Japan’s 1905 annexation of Korea and subsequent 40 years of colonial rule.

Similarly, the dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands/Las Malvinas, which broke out between Britain and Argentina in 1982, remains a constant source of diplomatic conflict.

But South China Sea lawsuits are difficult to defeat. All or part of this body of water is simultaneously called the South Sea (Nanhai) by China, the West Philippine Sea by the Philippines, the North Natuna Sea by Indonesia, and (alternatively) the East Sea (Biển Đông) by Vietnam. .

Further complicating matters in the same region, the islands commonly known as the Spratly Islands in English are also known as Nánshā QúndƎo in Chinese, Kepulauan Spratly in Malay, and Truường Sa in Vietnamese. is.

All the individual islands, rocks, and cays in this disputed region are named, individually or collectively, in multiple languages. Even the names of completely and permanently submerged features have proven controversial. Early British Admiralty cartographers were probably most accurate in naming the area simply “The Dangerous Lands.”

Protesters in the Philippines are celebrating the eighth anniversary of a court ruling that invalidated China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, locally known as the West Philippine Sea, in 2024. AAP

political divide

Globally, there is a movement to replace colonial references with original Indigenous names that are very familiar to Australians and New Zealanders.

In the same executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico, President Trump also renamed the highest mountain in North America (Alaska) from Denali to Mount McKinley (named in 1917 after the 25th president, William McKinley).

It simultaneously attacked the legacy of former President Barack Obama, who renamed the mountain peak Denali in 2015, and spoke to President Trump’s fight against perceived “woke” politics.

However, this change was tempered by the fact that the national park area surrounding the mountain would retain the name Denali National Park and Preserve.

Ultimately, President Trump could rename the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America, but only from a strictly U.S. perspective. It doesn’t seem to matter much to the rest of the world, except for those who want to curry favor with the new government.

Most countries around the world will continue to refer to the Gulf of Mexico. And the American Gulf may be lost to history in four years.