John Newcombe never planned to play the 1975 Australian Open.

At 30 years old, Newcombe was nearing retirement. He had played his home country’s major tournament almost every year since 1960, winning the championship in 1973 and reaching three other semifinals. He had also won Wimbledon three times and the U.S. Championships twice, as well as 16 Grand Slam doubles titles (he would add one more in 1976).

This year’s Australian Open, which begins on Sunday in Melbourne, marks the 50th anniversary of one of the most important matches of Newcombe’s career.

Newcombe was at home in Sydney when, in mid-December 1974, less than two weeks before the start of the ’75 Australian Open, he was informed by Tennis Australia, the tournament’s governing body, that Jimmy Connors, the defending champion, had entered the draw.

Connors, 22 years old at the time and ranked No. 1 in the world, and Newcombe had been waging war with each other, on and off the court, since their first encounter in the quarterfinals of the 1973 U.S. Open. Newcombe won that match en route to the title.

Newcombe was ranked No. 1 in 1970 and ’71, when rankings were determined by a group of journalists before the ATP established an official ranking system in 1973. He was also No. 1 briefly in 1974. Connors took over the top spot in ’74 when he won the Australian Open, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. He missed out on a chance for the Grand Slam — winning all four majors in a calendar year — that season when he was barred by the International Tennis Federation from playing the French Open because he had committed to playing World Team Tennis in the United States.

There was no shortage of verbal volleying between Connors and Newcombe, both members of the ATP’s recently formed No. 1 Club that includes 29 players who have achieved the top ranking. Newcombe accused Connors of pulling out of tournaments to avoid playing him. Connors fired back.

“Newcombe should do more talking with his racket and less with his mouth,” Connors said at the time. “He says I’ve been ducking him, but I don’t need to duck anybody. Every time I reach a final, he’s missing.”

Newcombe, now 80, was a disciple of the coach Harry Hopman. Newcombe, known for his Salvador Dali-type mustache and charismatic personality, possessed a powerful serve that propelled him to the net with ease. He could also play cagey backcourt tennis, drawing his opponents in with crafty drop shots and then flicking winning lobs over their heads.

“Newk was one of the most thoughtful, technical guys ever to play the game,” said Fred Stolle, 86, a fellow Australian, in an interview. He reached five successive major finals from 1964 to 1965, beating Tony Roche to win the French Championships (the precursor to the French Open) in ’65 and Newcombe to win the 1966 U.S. Championships.

“He could analyze the game better than anyone,” Stolle said. “He was one of the best thinkers out there.”

Connors, 72, was one of the early users of the two-handed backhand. With it, he raced across the base line, befuddling his opponents with perfectly placed short angle winners.

As soon as Newcombe learned that Connors would compete in the ’75 Australian Open, he wanted in as well.

“I told the tournament that if they could guarantee me that Jimmy was coming, then put me in the draw,” Newcombe said during a video call from his farm northwest of Sydney last month. “I hadn’t played for three or four weeks, so I had to do some quick preparation. I didn’t play much tennis, but I did a lot of running. I had a three-mile loop at our house in Sydney, and the last mile was a very steep hill. I called it Connors Hill, and I ran it in the middle of the day when it was like 90 degrees Fahrenheit. I’d get to the top of the hill, and I’d do like a Rocky jog at the top.”

Though seeded No. 2 behind Connors, Newcombe’s road to the final was arduous. He was taken to five sets by Rolf Gehring in the second round and also by Geoff Masters in the quarterfinals, a match that he won 10-8 in the fifth set. Afterward he needed a two-hour session with the physiotherapist to rejuvenate his weary legs.

His most challenging match came in the semifinals against Roche, a former French Championships winner who had reached five other major finals. Roche, the No. 3 seed, led 5-2 in the fifth set before Newcombe saved several match points and prevailed 6-4, 4-6, 6-4, 2-6, 11-9. There were no fifth-set tiebreakers played at the time.

“From 5-2 there was about 45 minutes more of the match that I have no memory of,” Newcombe said. “I’d never been in that sort of state before where I was so physically exhausted. It was like an out-of-world experience. But I knew that I had to win because I had to get to the finals against Jimmy.”

The final took place on New Year’s Day before a sold-out crowd of 12,500 at Kooyong Stadium.

“The whole of Australia was listening either on TV or on the radio,” Newcombe said. “The people at the beaches all had their radios tuned to the match. It had developed such a hype with this brash young American taking on the older Aussie who everyone liked.”

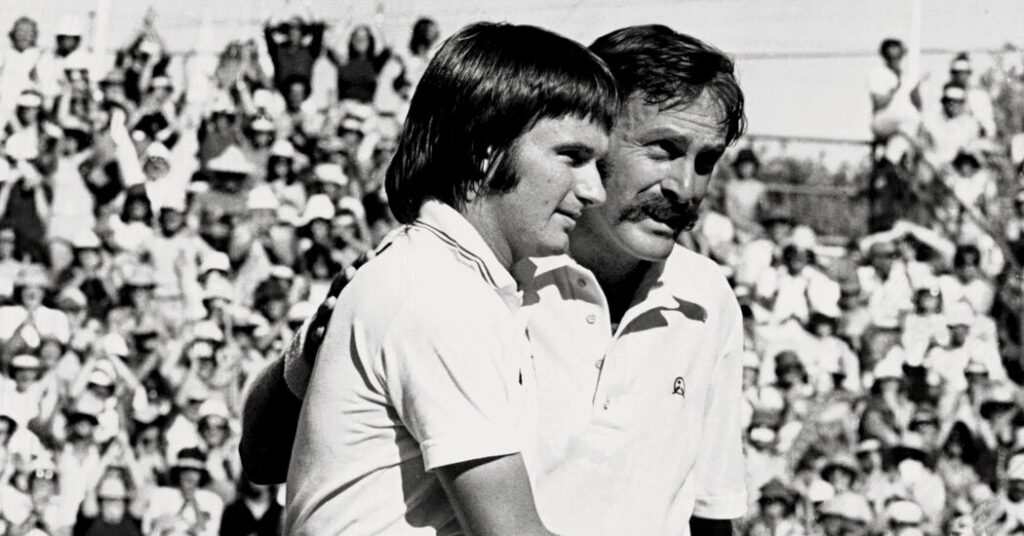

Connors had dropped just one set in his previous five matches and had not yet faced a seeded player. Newcombe admitted to being exhausted, exhilarated and determined. After his 7-5, 3-6, 6-4, 7-6 (7) victory, Newcombe jumped over the net, shook Connor’s hand and celebrated by having a quiet dinner with friends and then quickly falling asleep.

Connors and Newcombe would face each other again in 1975 in Las Vegas. Connors, who won that match, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Newcombe never won another major. His retirement in 1981 spelled the end of a three-decade run of Australian male dominance that included 17 victories in the Davis Cup team event from 1950 to 1977.

Because of the stewardship of Hopman, the longtime Davis Cup captain, and the example set by Roche, Newcombe, Rod Laver, Roy Emerson, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad and Neale Fraser, Australian male tennis thrived but then stalled until Pat Cash won Wimbledon in 1987.

Pat Rafter was a two-time U.S. Open champion in 1997 and 1998 and a two-time Wimbledon runner-up in 2000 and 2001. Lleyton Hewitt, the current Davis Cup captain, is the last Australian man to win a major when he captured the 2001 U.S. Open and 2002 Wimbledon title. Alex de Minaur is currently ranked in the world’s top 10, but he has not advanced beyond the quarterfinals at a major.

Australian women have been led by Margaret Smith Court (who is tied with Novak Djokovic with 24 major singles titles), Evonne Goolagong Cawley and Ashleigh Barty.

Newcombe said he believed that Australian tennis could shine again, but only if the Davis Cup regained its importance.

“When I traveled with Fraser and Laver and Emerson, I was hanging around champions,” said Newcombe, who was a member of five Australian championship Davis Cup teams from 1964 to 1973. “That rubs off on you. You see how they live and how they train and how they play their matches. So you start to think like a champion.

“We created a culture of ‘We can beat anyone anytime,’” added Newcombe, who, along with Connors, is in the International Tennis Hall of Fame. “When you do that, players start to believe and then exceed their own expectations and achieve the maximum of what they’re capable of. That’s what happened in our era and I believe we can get back there again.”