Today I was taking some time to think about the Confucian concept of being a gentleman, which should not be misconstrued as someone with eloquent speech who is dressed to the nines. We’re not excluding the ladies, either. You have to understand the context and take into account the time, place and era that these Confucian doctrines were made. It’s not to say that this concept is geared only towards men; it applies to people in general, so, you’re not off the hook. Everyone can act with a gentle demeanor, gentle meaning respectful and honorable towards everyone in all things. Now, that being said, let’s check ourselves and everyone around us. See how many people that you encounter today, literally today, who behave and conduct themselves in this magnanimous way. I would venture to say, because I live in New York City, that they are few and far between. But they are out there. They do exist and we should strive to be one of them.

I may be an idealist, but one of the main things that spurred me to learn martial arts was not any particular movie star or action series, but rather the ancient concept of the scholar warrior, the hero, the knight-like figure, as romantic as it may sound. I don’t mean romantic with a dozen roses, but rather the romantic notion of a heroic figure that would stand up for what is right, what is just, what is correct. Before we can even talk about the deeds that inspired these heroic stories/legends, myths, etc., we have to investigate where this idea comes from. I think it stems from ancient times in China’s long history and is tightly interwoven with the philosophical and social ideals that were prevalent at those times during the formation of the Middle Kingdom and their martial art traditions. Confucius taught many art forms, one of them being martial arts in the form of equestrian pursuits, archery and I believe even swordplay. He thought of that training as part and parcel with becoming the Superior Man or the 君子 “Junzi”. The original meaning of this term was a prince, someone of noble birth. In today’s sense, a gentleman is thought of as someone who is well-spoken, well-mannered and wears stylish clothing. I’m not saying that’s not it, but that’s still an exterior façade. In the true Confucian concept, 君子 “Junzi” has nothing to do with the status of which one is born, but rather the status of how one conducts themselves in their everyday lives. We’re actually talking about the character of the individual. The character of any individual, be they a martial art practitioner or not, is displayed and demonstrated solely by their deeds. Confucius said, “The superior man is modest in his speech but exceeds in his actions.”

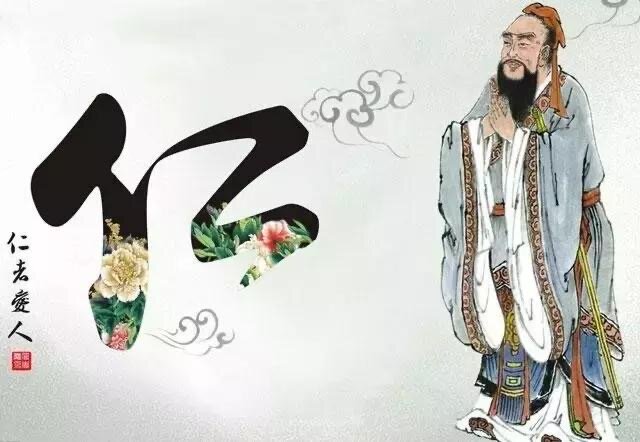

The Confucian concept of virtue is in line with the word 仁 Yan, which has been translated into many different words, benevolence, compassion, kindness, courtesy, goodness in the sense of a protective nature. The character 仁 is comprised of two distinct calligraphy characters, one meaning man and/or person and the second meaning “two.” It can be interpreted as how individuals should treat one another, or it can mean man and how man interacts with heaven and earth. Do you deal with things and treat people with a humanitarian sense and with a sense of love and caring? It’s about this philanthropic nature, doing things out of the kindness of your heart. This is at the core of the martial concept because the Chinese martial arts grew out of protecting not only oneself but one’s loved ones, family, country and beyond.

This is an essential quality of the martial artist in order to fulfill the ideals of what a Kung Fu practitioner should be. A fighter is not necessarily a martial artist while a martial artist does not necessarily have to be a fighter in the ring. So, the term “martial artist” I think is misunderstood and maligned by those individuals who don’t adopt, adhere to, understand, or uphold a particular code of ethics. As traditionally taught, a true martial artist has to embody this benevolent quality. If you’re going to train to be a martial artist, and stand up for what is right, it should be an integral part of your training.

Unfortunately, in modern martial art training, and mostly in recent times, the major concern has been the physical prowess of the individual and his ability to win a competition and/or defeat his opponent. I am by no means making light of this. This is also essential and a core precept, but cannot override the balancing point of ethical conduct and behavior. This is the balance that is struck between the warrior and the scholar, the two halves of the martial artist that make him whole. If one is nurtured over the other, then the individual will never fully realize his ultimate potential. That is, to become the superior man. This is what the training is all about, to empower and enlighten oneself so the individual becomes a better human being. If there’s no counterbalance in terms of a philosophical backbone behind what you’re training, then there’s no artistry in your martial arts. In the core of martial art training is built that the individual should be a good person and therefor contribute to the greater society.

This is the hard and the soft of it. How can you be a heroic figure without that balance between the hard and the soft? You see the grizzled war veteran on the battlefield, hands bloodied, (and again, I’m being super romantic so give me a little license) and he’s taken down all his enemies, but yet he has enough compassion to pick up the baby left on the side of the road during this tumultuous conflict and find it a place or save its life or rescue it from danger. You might be saying, “Oh come on, you watch too many movies,” but I’m sure it’s happened, not only in ages gone by, but in many modern confrontations. I think love in the sense of loving your fellow man because you’re able to see beyond the concerns of yourself is one of the grounding points of a real martial artist. The honor and respect that I learned and saw exemplified in previous generations has not trickled over as well as we would have hoped. This comes back down to the individual’s actions. Actions, as they say, speak louder than words. It’s how you carry yourself on a daily basis.

Am I benevolent and generous of spirit? Am I giving? We all have to question ourselves. I don’t work in a soup kitchen or engineer blood drives or work at the local PTA bake sale. Does this mean that I am not adhering to that Confucian concept of Yan? But these things can also be done in outward appearance, trying to manifest an image to make people believe that you are of this character. But it’s all a bold-faced lie, done to fool people, not from a genuine place. The Confucian concept is more about learning the self, not falsely doing deeds to create an image. I think the first thing that we need to do is put ourselves on the firing line and question ourselves before we point that high-powered firing line at someone else’s philosophical head. Today you have teachers, masters, professors, grand poohbahs of the lodge, self-proclaimed gurus and monks that say one thing and do another. “Do as I say, not as I do.” This is on the whole completely wrong and false. We as individuals, be it adults, parents, teachers, mentors, martial artists, must lead by example rather than just uttering these good words. And as I sit here and think about this, I wonder and think unto myself, “Hey you, you, too, have to live up to this on a daily basis. You can’t just say the things that should be said and do something else.” What can I do on a daily basis that encompasses these attributes?

I don’t have an answer for anyone. I don’t have a cure-all. I’m just making an observation, looking at things in general, looking at myself and looking back on this philosophical concept and wondering, how do we adhere or even begin to live with those precepts? As martial art people, we claim to have a code of conduct, high moral standards, ethics, but I don’t really see people living like that. Instead, like politics, martial arts often seems to appeal to those that desperately seek power over others. Martial art training and practice is not about power over others, but rather seeking virtue in all things. You seek to make yourself better so you make others better, and then you yourself are better. You seek to understand so you can help others understand, and therefor you gain greater understanding. I think it is very important for the martial artist to strive for this Yan, this compassionate, benevolent concern for not only himself but his fellow man that extends beyond blood and kin to all that he meets. If you don’t have genuine concern for others, then your martial art training is pretty much self-serving. And it is about the self, but rather growing beyond the self and being able to extend your knowledge, help, and experience, to others. Help others to grow and in that way help yourself to grow.

The real beginning, middle and end of it is, what does it take to be a real martial artist? The philosophical backbone of the Chinese martial arts is Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism. The Confucian concepts we’ve discussed teach a martial artist how to be humane, because if you’re not humane, you have no humanity; therefor, you’re a beast, and I’m not maligning animals. It teaches you how to be an individual and interact with others, and that’s what martial art training is all about. Isn’t it about being a better person? Being a better human means you have to have humanity. You have to have compassion, benevolence, respect, honor, care and love for everyone. That should be the example that we should all follow and that should permeate throughout our training. In one way, martial art training at its core is actually quite contrary to this precept of being humane and caring about others, but this is the counterbalance that has to be struck. That’s the hard and the soft that we mentioned before. You train this hard, unforgiving weapon, i.e. yourself, that you’ve been forged into, but it’s counter-balanced by the soft, the caring, the concern. You place value on human life and live a good life because you know how easy it is to hurt someone, to physically maim, to break someone’s bones, even to kill. But you don’t have the power to resurrect them and bring them back or even to make them whole, so why would you ever want to cross that line? No matter how hard you train, you have to temper it with compassion and forbearance for the human condition. That’s the point-counterpoint that we’re trying to make in this blog. That can’t be forgotten because once you forget this, then you’re not really a martial artist. You may be a combatant, but you’re never going to be able to live up to that Confucian ethical standard of the Superior Man, the one of noble spirit. Even though you have all the physical prowess, you lack the moral fiber, that heroic stature that we look upon and say, we want to be like this. So, what are the ingredients of a hero? There are many, but this is one of them.

– Sifu Paul Koh 高寶羅